Electric Lighting: The Housewife’s Moral Challenge

Figure 1: Frontispiece to ‘The Art of Decoration’ (1881)’

Technology’s Stories v. 8, no. 1 – DOI: 10.15763/jou.ts.2020.06.08.06

PDF: Harrison Moore_Housewifes Moral Challenge

Energy supply, like home design, in nineteenth century England was traditionally considered a decision for the “master” of the house. Yet a look at Mrs Haweis’ The Art of Decoration (1881), which includes one of the earliest print recommendations for the use of electricity to light the home, offers us a different vantage point. When she published her book, women were in fact making a wide range of energy decisions as electricity and gas could both be used for lighting and heating the home. Before the 1860s the choice of domestic furnishings seems to have been primarily a male activity.[1] The furniture and interiors trade was dominated by male upholsterers who would provide everything for the home, from sofas, to curtains and wallpapers. By the late 1870s however, consumption of domestic decoration and furnishing became an accepted and even expected activity for middle-class women. The home was both the space where most middle-class women spent the majority of their time, and the space in which they were expected to demonstrate their class and taste and by extension, morality. As the case of Mrs. Haweis shows, women started to offer guidance on these matters, including energy decisions. Different choices would create different interior effects, both in terms of the heat and light, and in terms of aesthetics and design. Mediators like Mrs Haweis therefore played an important role in facilitating the adoption of new energy technoogies, and in configuring those technologies in ways that were in keeping with the values and needs of women.

Mrs Mary Eliza Haweis (1848-1898) was an English author of books and essays marketed towards women. Her first book, as Mrs H.R. Haweis, was Chaucer for Children (1877), which she illustrated herself. In 1881, she combined the history of art and design with guidance for the nervous housewife tasked with furnishing her home in a style that would both reflect her personality and knowledge and “speak” correctly to her visitors. According to Adrian Forty, the home in the Victorian period “came to be regarded as a repository of virtues that were lost or denied in the world outside”. As England grew exponentially as a result of the industrial revolution, “the home stood for feeling, for sincerity, honesty, truth and love”.[2] Victorians frequently described their homes as a kind of heaven; women were urged to “strive to make a home something like a bright, serene, restful, joyful nook of heaven in an unheavenly world”.[3] Electric light certainly would make it brighter!The fear of getting their choices wrong led genteel women to turn to manuals like The Art of Decoration, which included a chapter devoted entirely to lighting and ventilation. Mrs. Haweis’s book is interesting because it shows women writing for women. Mrs Haweis’ book is interesting because it shows women writing for women at a time when they were beginning to become the key consumers of objects and decoration in the home. I want to explore the gendered challenge of producing the ‘house beautiful’, and hence the importance of these books being written by women and directed to women.

Mrs Haweis’s first section in The Art of Decoration is called “The Search after Beauty”, a discussion clearly influenced by John Ruskin’s Arts and Crafts credos, starting with a chapter called “The Art Revolt”. She starts by addressing genteel women, those able to afford the services of a decorator or designer, in their role as the arbiters of morality and beauty in the home by the 1880s; “Most people are now alive to the importance of beauty as a refining influence. The design of your home is not just about aesthetics and function, but about spirituality and care”.[4] She echoes English designers, A.W.N. Pugin and John Ruskin, who proposed that art and design could alter the attitude of a society broken by the social consequences of the industrial revolution. She argued “….the appetite for artistic instruction is even ravenous”, yet “the vacuum can be filled as easily as the purse can be emptied. Just now every shop bristles with the ready means: books, drawings and objets de vertu from all countries are within everyone’s reach, and all that is lacking is the cool power of choice.”[5]

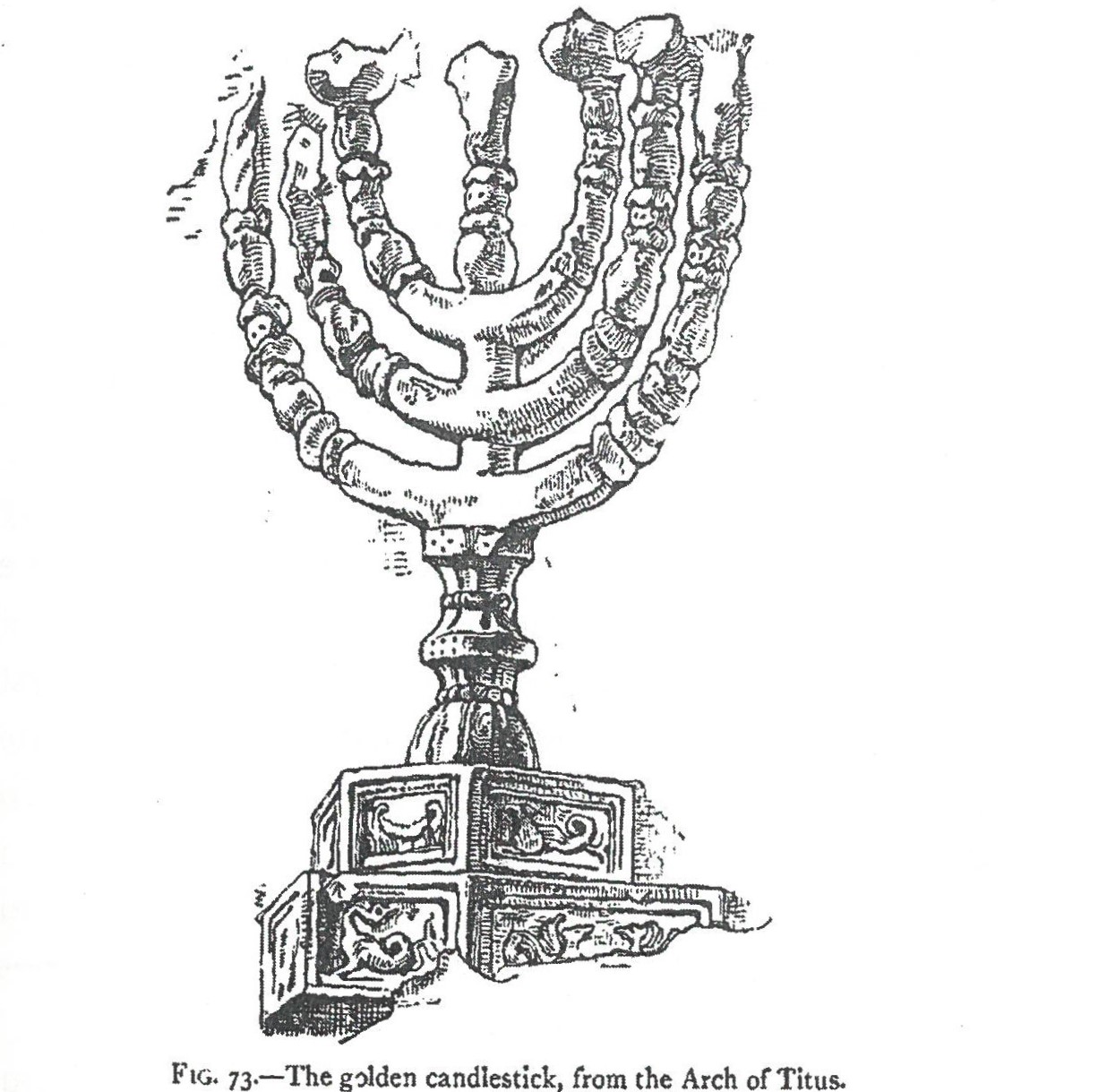

Figure 2. The Golden Candlestick’, in Mrs H. R. Haweis ‘The Art of Decoration’ (1881). No copyright.

Into this world of consumer goods, as described by Karl Marx in Capital (1867), came a group of women like Mrs. Haweis, some of whom publicly associated themselves with feminism and the suffrage movement, aiming to advise women to decorate their homes in a way that appealed to the concept of the duty of the woman to make the “house beautiful” for their family. The mass of shopping opportunities made guides like that of Mrs. Haweis vital, to help avoid social faux-pas, and confront the challenges presented by new technologies of energy supply and the very real concerns women had about their potentially devastating impact on their health and their beauty. The role of women as decorators and advisors to women as shoppers became key.[6] This is the role that Haweis frames for herself in The Art of Decoration; “It will be my endeavour to point out in these pages that choice remains, and to warn readers that beauty and art, like pure water, rely upon the tidal flow of new thoughts; they lie in no stagnant pool. The mind blindly accepts fashions simply because they are fashionable, without trying to discriminate in what the new is better than the old”.[7]

The idea that domestic décor was an expression of a woman’s personal character, was further linked with the idea of home as a reflection of and influence on a person’s morality, and the importance of cleanliness. For example, the sanitary reformer, Dr Southwood Smith, claimed that “A clean, fresh and well-ordered house exercises over its inmates a moral, no less than physical influence, and has a direct tendency to make the members of the family sober, peaceable, and considerate of the feelings and happiness of each other”.[8] These theories were brought to the public’s attention by “The International Preservation of Health and the Progress of Education” Exhibition held in London in 1884[9], launched with the bold claim that “At the moment there are no two subjects of greater importance to the nation than these.” Reformers argued that the rapid increase in population of England had a direct impact on health, “the houses even of the rich are hotbeds of disease, from the neglect of the most elementary sanitary laws”.[10] The rhetoric deployed in this exhibition made a clear link between beauty and health, and between a person’s surroundings and their character. “But how can persons who occupy miserable hovels…rise above their surroundings? How can they cultivate what might be termed the graces of life?”[11] they asked.

In Contrasts, Pugin had argued influentially that the architecture and design that surrounds us promotes behaviors, individually and collectively. Health was seen as “an attribute of the mind as much as of the body”. This idea was illustrated by the “important matter of warming and ventilating a house” and a display of domestic electric lighting at the International Preservation of Health exhibition that stressed that such lightingt was “clean” both in terms of emitting no dirt in comparison to gas or oil, and in terms of illuminating the dust in the corners of one’s home. Technologies that aided cleanliness, ventilation and orderliness were not enough on their own, it was argued,only the cultivation of beauty would arouse the higher feelings. Beauty was consistently attributed a moral value in addition to purely aesthetic significance.[12] Mrs Haweis saw this as being reflected in Arts and Crafts designs, which celebrated natural forms, the reality of their materials and the skill of the craftsperson.[13] This call for the design of lights to be equally as moral and as reflective of beauty can be heard in a 1904 article on “Electric Light and the Metal Crafts”; “One of the distinguishing characteristics of old-world design is an inimitable blending of the utilitarian and the beautiful in the production of those everyday articles [here with direct reference to electric lights] which we, in these degenerate and restless days, with few exceptions”. [14] The article goes on to quote Ruskin’s demand that, “we should ornament construction, and not construct ornament”, as a way to battle against degeneracy.

From the 1860s, a range of guides were published to decorating the beautiful, moral home, and alongside the popular texts by men such as Charles Eastlake’s Hints on Household Taste (1868) and Colonel Edis’s Decoration and Furnishing of Town Houses (1881), women began to guide their fellow sisters, including The Art of Decoration, Mrs Panton’s Suburban Residences and How to Circumvent Them (1896) and the Garrett cousins’ Suggestions for House Decoration (1879).[15] The arrival of professional interior decorators indicated a new attitude to home decorating. By the late nineteenth century there was a reaction against the upholsterer’s trade mentioned above, particularly from middle class intelligentsia, who deplored the failure of the upholsterers to provide decorative schemes which met with the moral and aesthetic standards of beauty they expected in their homes. ‘They were seen as trading in “dishonest” furniture which disguised the way it was made, or the materials of which it was made’. Objects that celebrated craftsmanship, materiality and function were seen as conforming to Christian values that domestic life should demonstrate.[16]

“Nowadays, a comparatively small expenditure is sufficient to provide a purchaser with things both satisfying to the cultured taste, and of suitability for any ordinary purpose. In the expenditure of a given sum on electric light fittings, this should be so apportioned that the best effect is produced in the best positions”.[17]

The housewife, as such was exhorted to be prudent with money, purchase “purely utilitarian lights [with] unpretentious and inexpensive fittings”, married with an arts and crafts aesthetic. The article concludes that “A jarring of styles should be avoided. What can be more incongruous than the mixture of Gothic or medieval wrought-iron fittings with the neo-classical lines and elegant details of French or English eighteenth century decoration?”[18] This picks up precisely on Mrs Haweis’s general theories on good design. Mrs Haweis’s guide to “lamp forms” celebrated craftsmanship, materiality and function as conforming to the Christian values that domestic life should demonstrate.[19] No material should imitate something that it is not and furnishings that obeyed the criteria of beauty, it was argued, were bound to have a good moral influence. Colonel Edis, for example, warned in 1883 against the dangers of “dishonest design…If you are content to teach a lie in your belongings, you can hardly wonder at petty deceits being practiced in other ways”.[20]

Given the date of publication, in 1881, at the very earliest period of electrification, only one year after William Armstrong had first lit up Cragside, it is unsurprising that Mrs. Haweis starts her chapter on lighting with the statement “Until the electric light is more manageable than is now is, there are two ways of lighting rooms – gas or lamps and candles”.[21] She goes on to focus her discussions on gas but points out its challenges, saying that although it was “the cheapest, and the least trouble…it is the most destructive to furniture and pictures, the least healthy and the least becoming”.[22] Mrs Haweis, like many of the decorators and suppliers of lighting at this time, considered the very oldest of lighting types as well as the newest, declaring that “Lamps are the next best, if they can be induced not to smell; wax candles are the best of all, if they can be warranted not to bow”. And so, for this author, advising women in 1881, the most traditional form of lighting was still one of the best.[23] She focused throughout the book on the idea of the natural and nature, including for lighting. “The main light ought to be concentrated as much as possible in one spot. This is nearest to a natural effect for the sun is never in two or three places at once, and will be found becoming to faces and the folds of dresses”. [24] Her comments speak directly to women, and the concern for appearance under different lighting types is key. “It should always be remembered that faces look best (if we may venture to disagree with Queen Elizabeth) with their natural shadows. Which give that ‘drawing’ to them always missed on the stage when the footlights glare up from below”.[25]

By 1900, efficient lighting remained a luxury in the UK and so Mrs Haweis, was very much ahead of the times[26] in concluding that, “When the electric light comes into common use, the problem how to light adequately a large room without heating it will be solved”.[27] For electricity to be adopted into the home, and chosen over alternative technologies, there needed to be a programme of persuasion in print to focus the consumer on the design and technological possibilities of adopting this energy source framed as moral, beautiful, and ultimately healthier, challenging a rhetoric of fear promoted by the gas companies of threat to the body and home and the aesthetic revulsion to electric light of many, especially women. Guides written by women like Mrs Haweis became vital; Mrs Haweis’s small section of her Art of Decoration is thus a pioneering piece of guidance to women thinking about how to light and power their homes in Great Britain in the 1880s.

Copyright 2020 by Abigail Harrison Moore

Abigail Harrison Moore is a Professor of Art History and Museum Studies in the School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies at the University of Leeds, UK. She is currently working on an international project to recover the histories of women and energy, with a particular focus on decision making in the home.

Suggested Reading

Mrs H.R. Haweis, The Art of Decoration, (London; Chatto and Windus, 1881).

Graeme Gooday, Domesticating Electricity, (London: Routledge, 2008).

Graeme Gooday and Abigail Harrison Moore ‘True Ornament? The Art and Industry of Electric Lighting in the Home, 1889-1902’, in Kate Nichols, Rebecca Wade and Gabriel Williams (eds) Art Versus Industry? New Perspectives on Visual and Industrial Cultures in Nineteenth-Century Britain, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015), 158-78.

Abigail Harrison Moore, ‘Designing Energy Use in a Rural Setting: A Case Study of Philip Webb at Standen’, in Abigail Harrison Moore and Ruth Sandwell (eds.) ‘Energy in the Countryside, 1850-1960: Social and Material Practices of Rural Energy Consumption’, History of Retailing and Consumption, Jan 2018 (1), 28-42.

Bea Howe, Arbiter of Elegance; A Victorian Biography, (London: Harvill Press, 1967).

[1] Adrian Forty, Objects of Desire. Design and Society since 1750, (London: Thames and Hudson, 1986), 105.

[2] Forty, Objects of Desire, 101.

[3] Baldwin Brown, Young Men and Maidens, A Pastoral for the Times, London 1871, pp.38-9 quoted in Forty, Objects of Desire, 103.

[4] Mrs H.R. Haweis, The Art of Decoration, (London; Chatto and Windus, 1881), 2.

[5] Haweis, The Art of Decoration, 2.

[6] See Graeme Gooday, Domesticating Electricity, (London: Routledge, 2008).

[7] Haweis, The Art of Decoration, 2.

[8] Quoted in Recreations of a Country Parson (London: 1861) 299

[9] Douglas Galton, “The International Health Exhibition”, The Art Journal, (May 1884), 154.

[10] Galton, ‘The International Health Exhibition’, 154.

[11] Galton, ‘The International Health Exhibition’, 154.

[12] Galton, ‘The International Health Exhibition’, 155; Forty, Objects of Desire, 109.

[13] On these points see Graeme Gooday and Abigail Harrison Moore “True Ornament? The Art and Industry of Electric Lighting in the Home, 1889-1902”, in Kate Nichols, Rebecca Wade and Gabriel Williams (eds) Art Versus Industry? New Perspectives on Visual and Industrial Cultures in Nineteenth-Century Britain, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015), 158-78.

[14] Art Journal, (Oct 1904), 321-8.

[15] Forty, Objects of Desire, 111.

[16] Forty, Objects of Desire, 112.

[17] “Electric Light and the Metal Crafts”, Art Journal, Oct 1904, 321-8, 323-4.

[18] “Electric Light and the Metal Crafts”, 232.

[19] Forty, Objects of Desire, 112.

[20] R.W.Edis, “Internal Decoration”, in Our Homes and How to Make them Healthy, ed. S.F Murphy, London 1883, p.356.

[21] Mrs Haweis, The Art of Decoration, 350.

[22] Mrs Haweis, The Art of Decoration, 350.

[23] Mrs Haweis, The Art of Decoration, 350.

[24] Mrs Haweis, The Art of Decoration, 350-1.

[25] Mrs Haweis, The Art of Decoration, 351-2.

[26] ‘There was a larger demand for lighting in Britain than in the less urbanised and less well-lit USA, but the lion’s share of the market in this country went to the gas industry. Byatt in “The British Electrical Industry, 1875-1914”, pp.56-7, calculated that in 1890/1 the gas companies share of the gas and electric market was 68% in the US, and almost 100% in England and Wales (Leslie Hannah, Electricity before Nationalisation: A Study of the Development of the Electricity Supply Industry in Britain to 1948, (London: Macmillan, 1979), 9).

[27] Mrs Haweis, The Art of Decoration, 353.