Driving “Jim Crow”: Cars and Race in the United States

Technology’s Stories v. 8, no. 2 – DOI: 10.15763/jou.ts.2020.09.28.05

The twentieth century saw the rise of the automobile as the most important consumer product and economic lever in the United States. Driving became a required expression of American nationalism and citizenship. Yet American car culture was also inextricably intertwined with race. The automobile emerged as an important economic, technological, aesthetic, and racial category of North American identity and modernity in the twentieth century.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the United States (U.S.) emerged as a white world power or “Jim Crow” nation.[1] In the period after the Civil War, the forced labor of convict leasing, debt peonage, and the chain gangs of building automobile roads, accompanied sharecropping as forms of racial economic exploitation that replaced slavery. Racial pseudo-science and eugenics provided the rationale for racial imperialism and colonialism. After 1899, the U.S. emerged from the Spanish-American War with overseas possessions and domestic indigenous reservations and black spatial segregation throughout the nation. Reaction against Reconstruction and African American citizenship and suffrage included federal ambivalence, the Ku Klux Klan, veneration of the Lost Cause, disenfranchisement and segregation, and the horror of lynching as a ritual of “making” and preserving “whiteness.” The postbellum era in the nation resembled the period before the Civil War in that antiblack sentiment prevailed. Neither freedom, birthright citizenship, nor the enfranchisement of African American men ennobled black Americans. Black Americans represented a stigmatized and caricatured Jim Crow demographic on whom white Americans could inflict physical injury and death with impunity. Scholar William E.B. Du Bois noted the nation’s “all-pervading desire to inculcate disdain for everything black, from Toussaint to the devil…”[2]

One of the twentieth century consequences of the history of slavery, blackface minstrelsy, and the overdetermination of the color line was the continuation and development of a vernacular that accompanied legal racial hierarchy and the status of outsider. For example, in the North, slums, ghettoes, and inner cities described black areas; and black neighborhoods in the South—products of local white supremacy with unpaved streets, underbounded, redlined, and across the railroad tracks–were branded as “Blacktown,” “coloredtown,” “the Bottom,” or “the quarters” among various colloquial expressions. White residential areas were collectively referred to as the suburbs.

In addition to language and vernacular, damning racial narratives were available in history, fiction, memoir, textbooks, and in northern admiration for the beauty of plantation landscapes and reconciliation of Confederate symbols. Yet during the Reconstruction era after the Civil War, 1865-1877, and even after the rise of the solid Democratic South at Redemption in 1877, scholars estimate that 2,000 black men served at the local, state, and federal levels throughout the South from 1870 to 1901.[3] But the [William A.] Dunning School of interpretation, led by the Columbia University historian, deemed the period of Black Reconstruction the worst mistake in American history. Indeed, D. W. Griffith’s silent spectacle, The Birth of a Nation, released in 1915, reinforced the Dunning historiography. American companies traded on blacks as servants with advertising logos such as Aunt Jemina for pancake mix, the rice of Uncle Ben, and Rastus, the avatar for Cream of Wheat. The nation’s mail service handled lynching postcards until 1909 and other pernicious representations of African Americans were popular. A popular theme of Florida postcards depicted naked black children as “alligator bait.”

Race and the automobile were the milieu for Amos ‘n’ Andy on the radio. The radio show began as a local WGN Chicago production in 1926 and in 1929 the series joined NBC reaching a national audience. The show became a sensation that increased the sales of radio sets and fueled commercial radio. Vaudeville veterans, Charles Correll (Andy) and Freeman Gosden (Amos), two white men, performed and wrote the show which remained on the air until the final broadcast on 25 November 1960. They portrayed southern black characters who migrated from the South to Harlem and established the Fresh Air taxicab service.[4]

The language of racial hierarchy pervaded national car culture and the automobile was a contested site of making race. Unlike the public transportation of trains, streetcars, and buses, the car represented a private transaction that challenged race, technology, and consumerism. While black labor, organized in the form of convict leasing and the chain gang under white supervision, built southern roads, the performance of black motoring, independent of whiteness, evoked white anxiety. The car conjured the dare of black mobility and black bicycling and motoring became a source of white vigilance. Mobility in the post-Civil War era suggested black economic and geographic (dis)placement, the potential for social, economic, and political elevation, and generally, a loss of white control. Automobile trade journals in 1923 agreed that “illiterate, immigrant, Negro and other families” were “obviously outside” the market for the automobile.[5] Yet, by definition, Atlantic automobility did not remain exclusively within the domain of whiteness.[6] From the turn of the century it was visibly clear that black Americans were driving and black motoring has remained a source of racial tension.[7]

Black and white Americans drove the automobile into the twentieth century and it symbolized the manners and habits of the new century. The automobile also represented the dialectic of race. For African Americans, the automobile provided mobility and citizenship. For white Americans, car culture was available to reproduce the violence of Jim Crow.

Historian Edward Ayers remembered the casual violence of white racial vernacular. He wrote,

[W]e lived in a…culture of white supremacy [that] thoroughly saturated us. People I knew did not hesitate to identify bright colors as “nigger colors” and big sedans as “nigger cars.” It was not uncommon to see signs that caricatured black men enjoying watermelon. Downtown, signs identified the colored entrances to the Strand and theState theaters around to the side, leading to the balcony. When we white boys fought, we charged that two on one was nigger fun; when we had to decide the last one chosen for ball, eenie meenie mini mo ended with a nigger’s toe. When we wanted to frighten our younger siblings, we told them a big nigger was coming to get them. We thought nothing of it.[8]

Ayers’s passage revealed the race-making performances and expressions of anti-black sentiment that supported Jim Crow segregation. These racial and auto evaluations instructed and authorized the individual and collective white community to fear, degrade, and “other” black Americans. It was a rhetorical technology that justified racial inequality.

Journalist Paul Hemphill (1936-2009) recalled that his childhood in Birmingham, Alabama included narratives of Christmas stockings with black nuts called “nigger toes” and announcing “nigger soccer” among his friends meant that customary game regulations were suspended. His parents denigrated African Americans routinely and,

on Christmas afternoons, after we had stuffed ourselves with the white meat and the rest of the good stuff, my mother would wrap a plate of leftover turkey and dressing and we would get into the car and drive over to the ragged hill village of Zion City and honk the horn, and presently Louvenia would come out and walk across the bare dirt yard in frayed slippers and the only dress I had ever seen her wear, her relatives watching in silence from the porch. And she would fall into ingratiating exultations of joy over this wonderful gift…as my mother passed the plate to her through the window…and reminded her to bring the plate back on Monday…Presently, Daddy would wave to the crowd on the porch and crank the car and we would spin away, trailing dust, feeling good.[9]

The Hemphill family employed Louvenia as domestic help which also enabled Southern race-making. The family’s use of black household labor reified their Southern whiteness and respectability. In this holiday ritual the family used the car as an instrument of caste.

Florida native son Stetson Kennedy (1916-2011) was born in Jacksonville. In two interviews recorded in the 1980s, “Stet,” a shortened form of his mother’s family name, as he was sometimes called, remembered Jim Crow practices involving the auto. The performance of the “drive-by” as an expression of white male adolescent aggression comprised part of what he described as American Apartheid:

At around sixteen, I began writing poetry about Florida subjects and nature and people, impoverished people for the most part. My classmates and siblings were asking questions like, “What got into Stet?” What got into me was, for example, that one of the favorite sports of my classmates in [Robert E. Lee] high school was to drive by black delivery boys on their bicycle[s]; they would drive close to them and knock them off their bikes with all the groceries. That sort of thing did not appeal to me and prompted my writing and the question, “What got into Stet?” The mother of a classmate asked me, “Must you write about such things?”[10]

The Jacksonville drive-by phenomenon was a form of local high school white supremacy that used the motorcar as a weapon against black bicyclists.

The customary violence of lynching, segregation and disenfranchisement, the degradation of blackness in popular culture, and racial vernacular instructed and encouraged white male youth to devise and participate in Jim Crow practices directed at African Americans. For white youth these activities were significant as rites of passage and initiation into the gender roles of white supremacy.[11] In her study of white child-rearing, historian Kristina DuRocher noted the strategy of language and the power of address required to maintain Jim Crow racial boundaries.[12] Southern white child-rearing also recognized that the responsibility for pushing Jim Crow into the future belonged to white youth. She observed that, “…white boys, by their teenage years, understood the need to enforce African Americans’ subordination with violence.”[13] The Jacksonville drive-by phenomenon was a variation of local white supremacy. Paul Hemphill recalled, “It would have been perfectly all right for me to casually use the word ‘nigger’ around the house…and I might even have been rewarded with a smile and a pat on the head from my father as an acknowledgment that I was growing up just fine.”[14] It was similar to the transmission and assimilation of slaveholding practices in Southern antebellum families and communities a century earlier.[15]

At the end of the 1950s and the height of the Cold War, a national narrative of African Americans and cars remained current. Sociologist I. Roger Yoshino, a scholar at the University of Arizona, Tucson, observed the intersection of race and cars when he published a study that derived from the perennial student question of those enrolled in race relations classes: “Why is it that so many Negroes drive Cadillacs?”[16] The study concluded that the assumption of “the Negro and his Cadillac” proved unfounded.[17] We can surmise that racial automobile narratives marked white surveillance of black consumption. Just as the so-called “racial trait” of African American over-appreciation of foods such as fried chicken and watermelon obscured black poverty that did not admit adequate diets,[18] the pejorative narrative that mocked African Americans as extravagant for buying expensive Cadillacs defied the economic status of most black Americans and veiled a white desire for black immobility.

The blackface trope of black Americans and their louche longing for expensive cars revealed the significance of the automobile as a marker of status. The trope invests the Cadillac as too expensive for blacks and thereby an indication of black poverty contrasted with white affluence; and defines the Cadillac as exclusively for whites. These symbols of race and cars circulated to discredit African American claims to nationalism and citizenship throughout the twentieth century and in response to the Civil Rights Movement. For black Americans, the embrace of the motor car represented mobility, an unwillingness to comply with the dominant requirement of invisibility, and demonstrated black technological and economic assimilation. The racial trope of black Americans and their ostensibly greedy and unearned desire for material comforts, especially expensive Cadillac cars, revealed white anxiety evoked by black economic stability and their status as consumers.

In his examination of African American memory during the long twentieth century from the Second World War, historian Jonathan Holloway revealed the family motor car as a venue for difficult father-son conversations. During his adolescence in the 1980s Holloway routinely took the bus to school but when his father drove him to school, the drives were about his father’s struggle to find ways to speak to his son about the dangers of race. Holloway remembered two of these lessons were about sex and fighting. Yet, Holloway’s father did not relish these conversations and the occasions were chosen because of their brevity. The importance of the lessons lay in their intergenerational familiarity.[19] As for many Americans, the venue of the conversations, the automobile, was an extension of the Holloway family arrangement and provided additional space for collective intimacy. The Holloway narrative also illustrates how African Americans used the automobile as a technology of mobility and modernity, nationalism, and citizenship. African Americans used the car to negotiate and challenge caste and resist subordination.

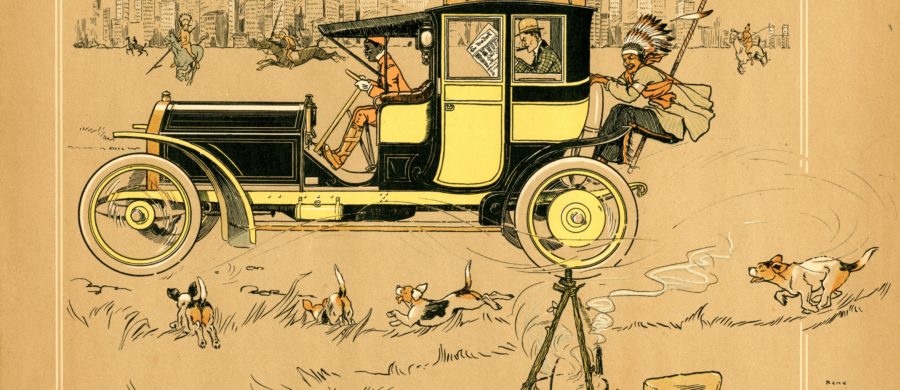

The images I have included in the text demonstrate a narrative of race and motoring that was consistent with Jim Crow practice. Figure 1 is a cartoon that featured two immigrants in traditional and modest grooming and attire. The cartoonist observed the popularity of automobiles among immigrants from Asia and southern and eastern Europe before the introduction of the Ford Model T and the organization of General Motors (GM) both in 1908. Early on, driving functioned as a process of assimilation or initiation into American life.

Source: Gene Carr (1881-1959), “Why, even the Ginnies and the Chinks is got autos these days!” Automobile Topics, Vol. VIII, No. 7 (May 28, 1904), 525, NAHC.

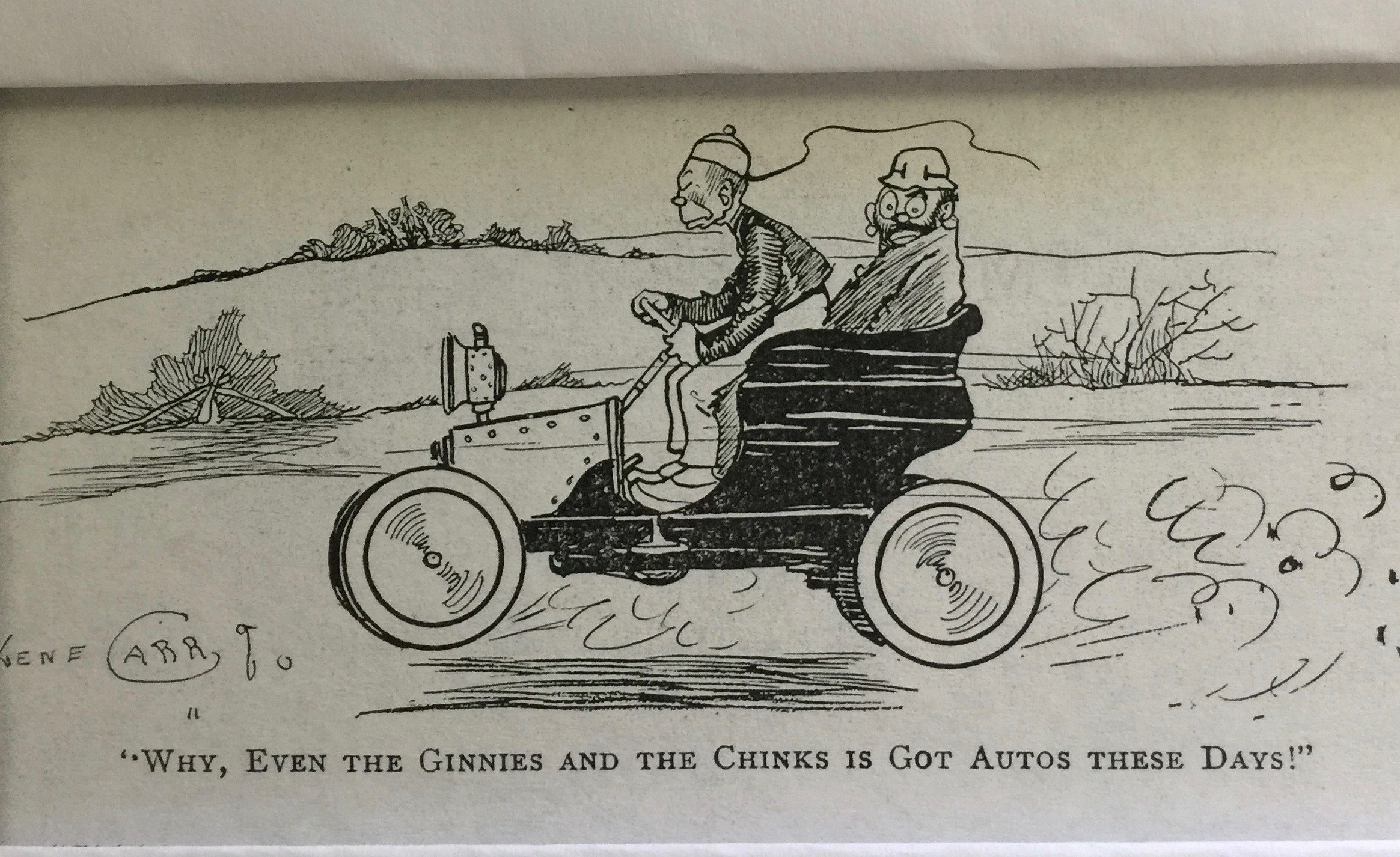

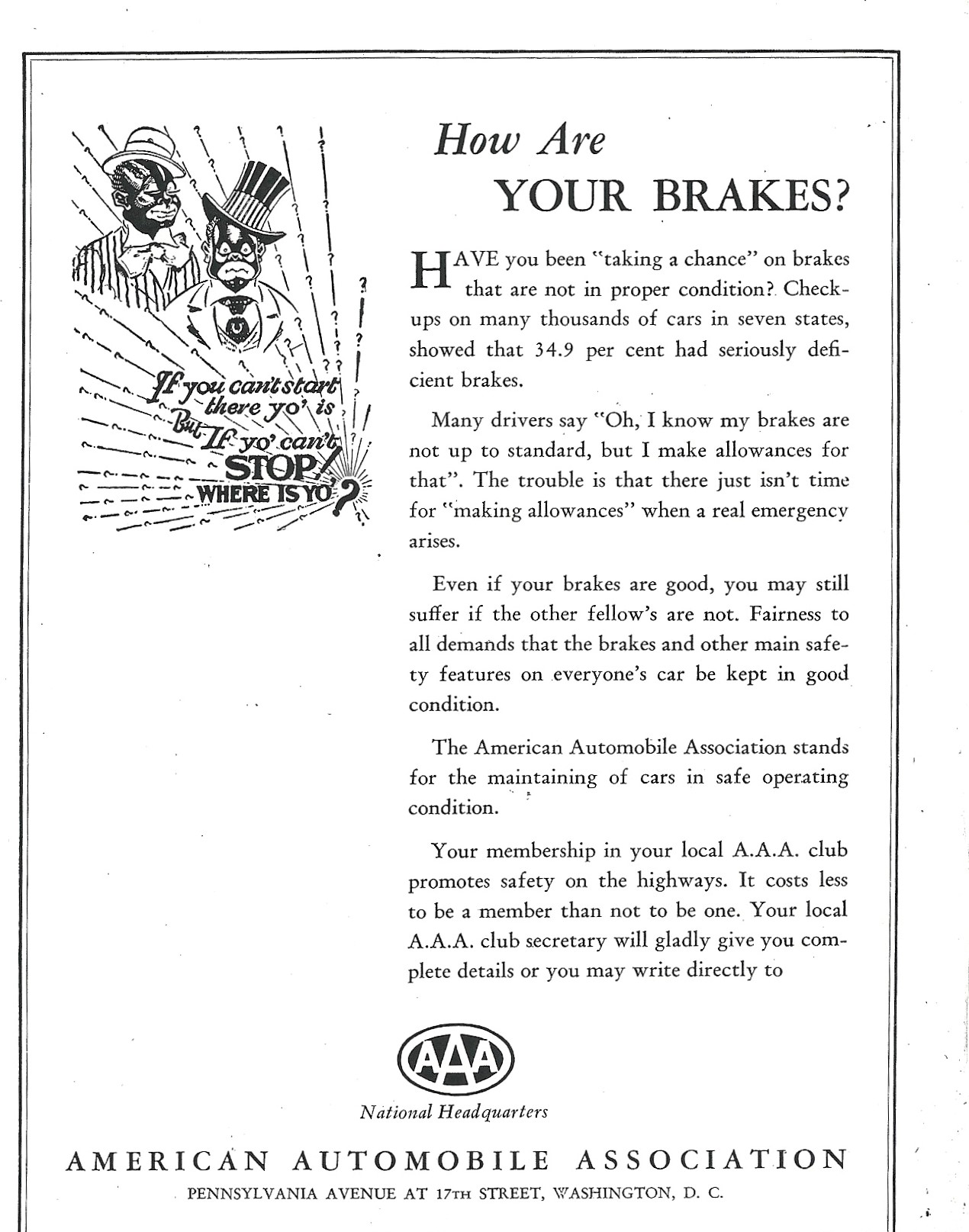

Figure 2 features Chicago, one of five cities in an ad series including London, Paris, Nurnberg, and Bombay (Mumbai) in a French ad series from the first decade of the twentieth century. The black American chauffeur was both porter and servant. The black body was contained in the uniform and the machine; the Native Americans were imagined as “noble savages” unrestrained by civilization. The figure of the black chauffeur has been and remains pervasive in American literature into the twentieth-first century. The ad series also marked Atlantic and colonial automobility.

Source: Automobile sales catalog, Rene Vincent (1879-1936), Automobiles Berliet, Lyon-Monplaisir, France, 1906, The Collier Automobile Museum and Research Library/Revs Institute, Naples, Florida.

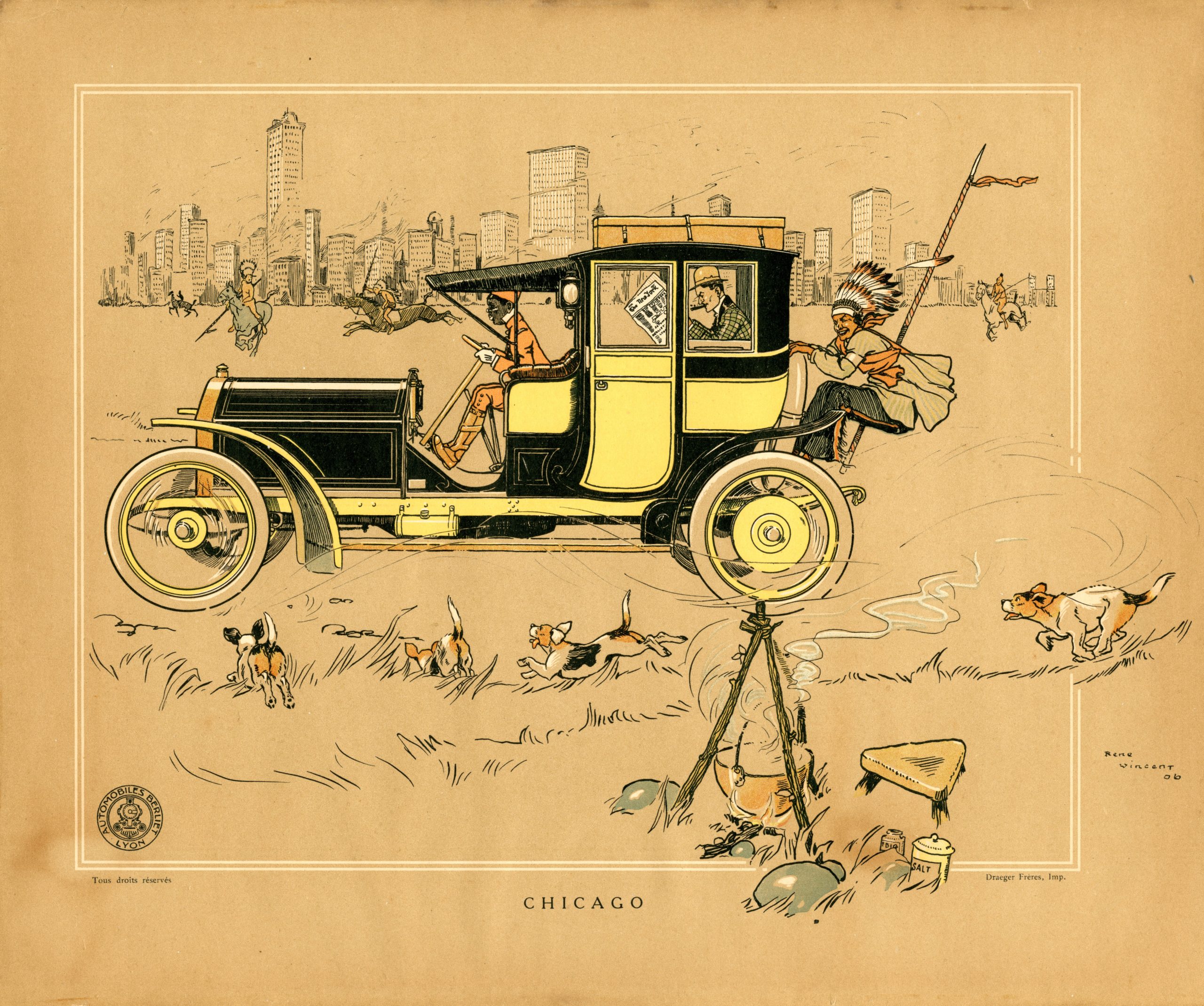

The third image is a page from American Motorist, the official monthly publication of the American Automobile Association (AAA) in 1935. The organization was established in 1902 and excluded black membership. In an ad reminding the membership to regularly check the brakes on their cars, the text featured two black men drawn overdressed and dandified and their speech was rendered in blackface:

“If you can’t start[,] there yo’ is—But if yo’ can’t stop! Where is yo’?”

This racial trope of black inferiority accused African Americans of not speaking fluent English, speaking in malapropisms, and occupying a status of language-impairment and unintelligibility. This particular racial disparity, theoretically, audibly demonstrated black unfitness for citizenship and community. The blackface voices and representations in the ad indicated that African Americans were ineligible for AAA membership, and the status of AAA membership was “for whites only.”

Source: “How are your brakes?” American Motorist, Vol. V, No. 4 (January,1935), 1, American Automobile Association Archive, AAA Headquarters, Heathrow, Florida.

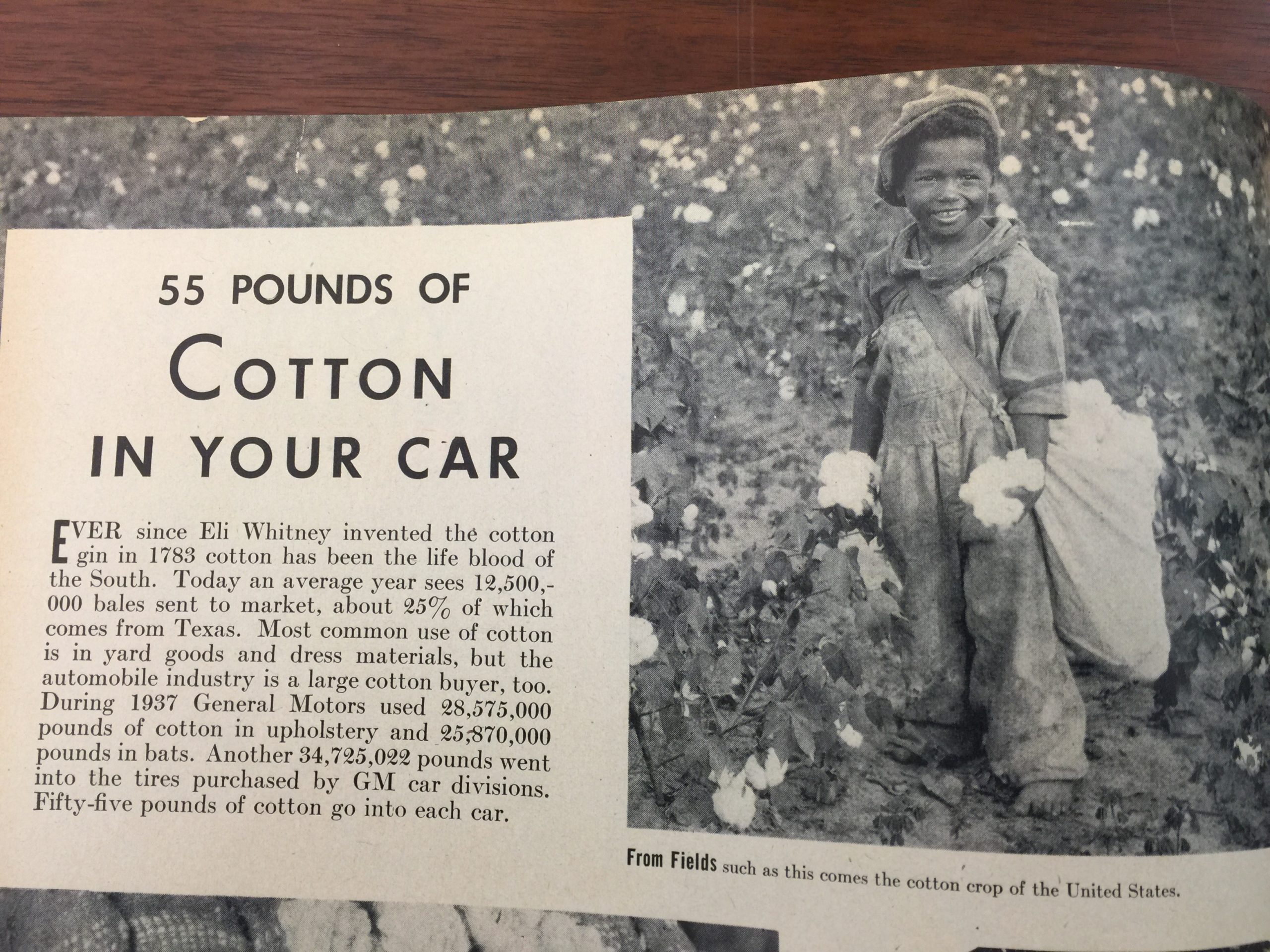

The fourth figure is taken from a GM publication in 1938. The introductory photograph features a small black male child dressed in dirty overalls, a cap, bare-footed, and with a full cotton-picking bag slung over his shoulder. Despite the poverty of the circumstances and the short school year for Southern black children, the child is adorable and his charisma is apparent; but that is not the point. In 1938 the photo was meant to evoke an ethos of sentimentality and nostalgia for the Old South. A century earlier enslaved black children performed the same task. The other eleven photos of the two-page article identified machines used in processing the raw cotton and turning it into upholstery cloth and batting and show white workers performing various tasks in cotton processing but none of the factory workers were black. White women were employed in one photo as operators who inspected the finished goods. The introductory photograph and its brief text reminded and reassured the majority white readers of the company journal that they participated in and derived benefits from making whiteness.

Source: “55 Pounds of Cotton in Your Car,” GM Folks!, Vol. 1, No. 4 (August, 1938), n.p., General Motors Heritage Center, Sterling Heights, Michigan.

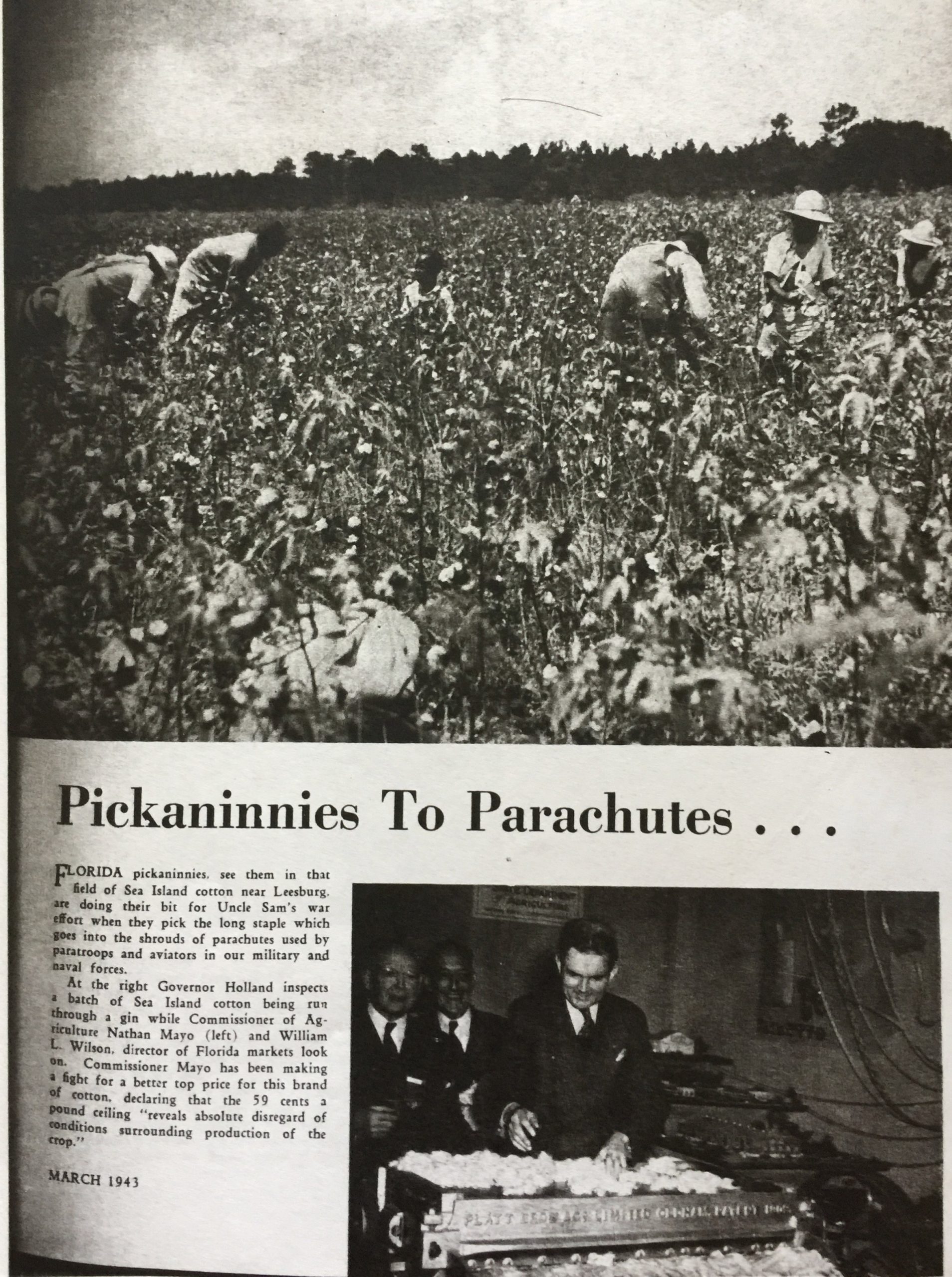

The final figure is a photograph from Florida Highways, the official monthly publication of the State Road Department established in 1915; the journal began in December 1923.[20] This introductory photograph also echoed the Old South symbol of black bodies in cotton fields. The title of the article, “Pickaninnies to Parachutes…,” used alliteration to mark the demeaning term “pickaninnies”[21] to describe Florida black citizens and soldiers in a time of war. The article noted the transformation of Florida-grown cotton into war materiel at the expense of the dignity of the black citizen, laborer and soldier.

Source: “Pickaninnies To Parachutes…,” Florida Highways, Vol. 11, No. 4 (March 1943), 25, 27, Florida Special Collections, State Library and Archives of Florida, Tallahassee, Florida.

The cartoon, illustrations, photography, language and vernacular reveal a blackface discourse about African Americans, and sometimes immigrant ethnics, that sought to compel them, and the nation, to “drive Jim Crow.” For white Americans, “driving Jim Crow” was a way to use the auto as a weapon to enforce racial caste. In 1945 African American writer Chester Himes and his wife relocated from New York City to northern California after the publication of his first novel, If He Hollers Let Him Go. The couple bought a new Mercury and drove from New York to San Francisco via the Lincoln Highway. Between The Empire State and the Golden State they “found no place where we could sit down to a table and have a meal.” Himes observed that anti-black “race prejudice and hatred” in the nation was “brutal, vicious and frightening.”[22] The Montgomery Bus Boycott a decade later in Alabama also marked the paradox of American democracy and colonialism.

Yet, simultaneously, automobility enabled African Americans to experience and enjoy twentieth century modernity despite the unrelenting violence of Jim Crow. Perhaps Himes was not aware of The Negro Motorist Green Book that began publication in 1936. Black publisher Victor H. Green (1892-1960) provided state-by-state listings of hotels and tourist homes, restaurants and diners, bars, cleaners, barber and beauty shops, gas stations and garages, and other amenities that were available to African Americans. The formerly obscure Green Book, published until 1966, represented a civil counter-narrative to the ubiquity of blackface representations of African Americans as justification for their exclusion and has been celebrated in popular culture in the twenty-first century.[23]

In her study of motoring and Civil Rights, historian Gretchen Sorin suggested that African Americans used automobile travel as a weapon against Jim Crow disadvantage.[24] The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination in public facilities and accommodations and rendered the Green Book a relic. The term “driving Jim Crow” identifies the centrality of the automobile in American life in the twentieth century and its contested terrain of racial competition, exclusionary practices, and mobility. The American automobile emerged in a profoundly racialized society and reproduced Jim Crow in car culture.

Fon L. Gordon, Ph.D. is associate professor and coordinator of Africana Studies at the University of Central Florida.

Suggested reading list:

Essays:

Gilroy, Paul. “Driving While Black.” In Car Cultures, edited by Daniel Miller, 81-104. Oxford and New York: Berg, 2001.

Books:

Carpio, Genevieve. Collisions at the Crossroads: How Place and Mobility Make Race. Oakland: University of California Press, 2019.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. 1925.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow. New York: Penguin Press, 2019.

Glasgow, Ellen. In This Our Life. 1941.

Gilroy, Paul. Darker than Blue: On the Moral Economies of Black Atlantic Culture. Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010.

Nevels, Cynthia Skove. Lynching to Belong: Claiming Whiteness Through Racial Violence. College Station: Texas A&M University, 2007.

Seiler, Cotton. Republic of Drivers: A Cultural History of Automobility in America. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Seo, Sarah A. Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed American Freedom. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2019.

Sorin, Gretchen. Driving While Black: African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights. New York and London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2020.

Taylor, Candacy. Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America. New York: Abrams Press, 2020.

Copyright 2020 Fon Gordon

ENDNOTES

[1] A term from the blackface minstrel stage of the antebellum era, Jim Crow was a dance step, a popular song, and an obsequious demeanor inhabited by blacks, whether enslaved or free, in the white imagination. In the period after the Civil War the term was re-purposed to identify state and federal legislation, industry-wide policies, and Supreme Court decisions that nullified the Reconstruction Amendments.

[2] W.E.Burghardt Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903; New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1979), 6.

[3] Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow (New York: Penguin Press, 2019), 8.

[4] Melvin Patrick Ely, The Adventures of Amos ‘n’ Andy: A Social History of An American Phenomenon (New York: The Free Press, 1991), 2-4, 8.

[5] James J. Flink, The Automobile Age (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The MIT Press, 1988), 131.

[6] See Gijs Mom, Atlantic Automobility: Emergence and Persistence of the Car, 1895-1940 (New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2015).

[7] “Homeward Bound from the Fair,” The Automobile, Vol. XI, No. 13 (September 24, 1904), 362, National Automotive History Collection (NAHC), Skillman Branch, Detroit Public Library, Detroit, Michigan; “Automobiles and the Jim-Crow Regulations (1924),” in Hammer in Their Hands: A Documentary History of Technology and the African-American Experience, ed. Carroll Pursell (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 211; “Jim-Crow,” Crisis 36, no. 2 (February, 1929), 66; F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (New York: Scribner, 1925; 2003), 73, 147.

[8] Edward L. Ayers, “Pieces of a Southern Autobiography,” in What Caused the Civil War? Reflections on the South and Southern History (New York: WW Norton & Company, 2005), 15-16; See also David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London and New York: Verso, 1991; 2002), 3.

[9] Paul Hemphill, Leaving Birmingham: Notes of a Native Son (Tuscaloosa & London: The University of Alabama Press, 1993), 61-62.

[10] “Stetson Kennedy Interview with Kevin McCarthy, 3 August 1988, Fruit Cove, Florida,” 3, Folder 2/22, Box 6 and “Interview Number FP48A, Interviewee Stetson Kennedy, Interviewer Gary Mormino, 23 January 1986,” 1-2, 5, Folder 1/22, Box 6, Stetson Kennedy Papers, Special Collections, Tampa Library, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida.

[11] W. Fitzhugh Brundage, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880-1930 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 2.

[12] Kristina DuRocher, Raising Racists: The Socialization of White Children in the Jim Crow South (Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 2011), 21.

[13] Ibid., 33. See also Jennifer Ritterhouse, Growing Up Jim Crow: How Black and White Southern Children Learned Race (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

[14] Hemphill, Leaving Birmingham, 61.

[15] Just as Southern parents taught their children how to enforce black subordination in the Jim Crow era of the twentieth century, antebellum generations of slaveholding parents taught their daughters and sons how to administer the “peculiar institution” of slavery. Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2019).

[16] I. Roger Yoshino, “The Stereotype of the Negro and His High-Priced Car,” Sociology and Social Research, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Nov-Dec 1959), 112.

[17] Ibid., 112-118.

[18] Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers,1944), 964; Psyche A. Williams-Forson, Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

[19] Jonathan Scott Holloway, Jim Crow Wisdom: Memory and Identity in Black America Since 1940 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 6-13.

[20] Fon L. Gordon, “Early Motoring in Florida: Making Car Culture and Race in the New South, 1903-1943,” Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 95, No. 4 (Spring 2017), 534.

[21] Pickaninny was used around the Atlantic world colloquially to refer to a black, and, hence, enslaved child, derived from Portuguese pidgin in the patois of the slave trade from the seventeenth century. In the United States, the term evoked Deep South romantic sentiment.

[22] Chester Himes, The Quality of Hurt: The Autobiography of Chester Himes Volume I (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1971, 1972), 78.

[23] See: Candacy Taylor, Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America (New York: Abrams Press, 2020); The Green Book: Guide to Freedom, directed by Yoruba Richen (Smithsonian Channel, 2020), 51m.; Green Book, directed by Peter Farrelly (Universal, 2018) won the Best Picture Oscar at the 91st Academy Awards in 2019; Calvin Alexander Ramsey, Ruth and the Green Book (2010) and The Green Book: A Play (2006); Celia McGee, “The Open Road Wasn’t Quite Open to All,” New York Times, August 22, 2010; Kaitlyn Greenidge, “A Black Motorists’ Guide to Jim Crow America, Newly Relevant,” New York Times, October 18, 2018.

[24] Gretchen Sorin, Driving While Black: African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights (New York and London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2020), 16-17.