Aesthetics and the Political Appropriation of the Electric Light

Technology’s Stories v. 8, no. 1 – DOI: 10.15763/jou.ts.2020.06.08.01

Walking the streets of Madrid at dusk is a splendid occasion to encounter the dazzling night life of a European capital that never sleeps. However, I found it particularly striking to stumble across a tiny chapel hiding in a corner of one of the main shopping boulevards of the city, otherwise dominated by cafes, restaurants and shops. It was nearly 10 pm and city lights were starting to spread their glare together with the glowing display windows of shops. To my surprise, these urban and commercial lights mingled with some bright blue neon light coming from this little chapel. It seemed to me as if this somewhat profane, yet “sacred” illumination was trying to fight back or resist the other lights. Indeed, the sign at its very entrance stated that the chapel was intended to be “an oasis of silence and prayer at the centre of Madrid”.

Figure 1. A stroll through Madrid. A tiny chapel at the corner of Fuencarral and Augusto Figueroa Streets. Photo by author.

I exchanged a few words with the priest in charge, who told me that the neon lights were precisely aimed at “fighting fire with fire”, attracting people “by any means, as the lights of the shopping display windows do”. He then urged me to visit another spot, just two blocks from there, where I discovered a bigger church with an even more generous display of electric lights outdoors.

Figure 2. Church of St. Anton or ‘Father Angel’s church’, Hortaleza Street, Madrid. Photo by author.

This apparently “mundane” use of illumination intrigued me. Yet, this trend of captivating the senses through the appropriation of everyday technologies for religious purposes is nothing new in the history of the Spanish Catholic church. One hundred and forty years ago, during the Restoration of the Bourbons era (1874-1930), the institution went through a similar process in which it had to confront and negotiate with technological modernity, resulting in the strategic instrumentalization of electric lights. Of course, that operation was not exempt from controversy since it sparked both enthusiasm and severe criticism from within the Catholic community and beyond.

Technology, the Catholic Church and the dynamics of innovation

The research on religious approaches to electrification in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries demonstrates how religious authorities and practitioners discussed the acceptable or unacceptable uses of electricity and electrical technologies. The case of the Spanish Catholic church at the turn of the twentieth century is just one example of the ways in which religious communities have historically interpreted new technologies from within the framework of their beliefs and practices.[1]

Initial reactions to electricity were diverse and practitioners made distinct decisions about its permissibility and adoption, adaptation or rejection. In this regard, religious communities were not monolithic; differences inevitably arose with highly visible and sometimes contradictory positions emerging in the process. Thus, conversations about electricity and its various meanings resulted in a plurality of views on the possibilities of religious reformation, the observance of traditional values or questions as to how religious communities should engage with different types of modernity.[2]

In the case of the Catholic church in nineteenth century, its responses to electrical innovation were originally shaped by the stance of the Vatican Curia which, in turn, was deeply concerned about the development and impact of “modern” science and technology; most importantly, they were worried about the new rationality they heralded and their threat to the Church’s cultural hegemony. It is certainly well known that Catholic intransigence towards modernization led to the Syllabus of Pope Pius IX in 1864, expressing the absolute refusal to reconcile with the principles of “civilisation and the modern world”, amid the intense process of secularisation in many parts of Europe.

However, Pius IX lifted the technophobic prohibitions of Pope Gregory XVI (1831-1846), including the condemnation of the telegraph, and helped the modernisation of the Papal States. Hence, the encounters with the technological dimension of modernity were more complex than they at first appeared. This idea encourages us to move beyond binary conceptions marked by the eternal dichotomy between “modern” and “anti-modern” forces, i.e. confrontation or plain appropriation of new technologies.

Technophobic attitudes, strident as they might have been, were very often more rhetorical than real and did not necessarily represent Catholicism as a whole. In fact, many priests and practitioners genuinely believed that some rapprochement with the modern world was necessary and, in this vein, techno-scientific advancements were instrumental to this goal.[3]

Figure 3. Pope Pius IX (1792 – 1878). He contributed to the modernization of the Papal States through railroad and telegraph networks. Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Pope_Pius_IX_(4671806).jpg, downloaded December 30, 2019, 0800 GMT. In the public domain.

This diversity of perspectives applies to the Spanish case. Although its ideological enemies repeatedly mentioned the reactionary nature of the Spanish Catholic church – blaming it for the underdevelopment and scientific underperformance of the country at the end of nineteenth century –, the institution showed an impressive capacity for renewal, even by using “modern” strategies and tools.[4] It is worth noting that this process of updating occurred during a crucial moment in the history of Spanish Catholicism. Indeed, the Restoration of the Bourbons era – especially the 1890-1914 period – was characterized by growing secular-Catholic tensions amid vehement anticlerical campaigns which galvanized different opposition forces, including anarchists, socialists, republicans and democrats.[5] Therefore, the Church’s hegemonic position was being fiercely eroded, even in a terrain until then regarded as belonging to it: the streets. In such a defensive context, and with an increasingly independent public opinion, the institution had to develop new tactics, including the strategic appropriation of science and technology.[6]

But how did the Catholic church approach the electrical technologies and the possibilities of an electrified future? At a time when the “profane lights” of modern cities, display windows or theatres evoked a modernity regarded with suspicion, the religious aesthetic framework was used to “tame” electricity and its potential uses, at least within a space of highly importance for the community: the churches. There, electric lights should fit into the traditional meanings of religious illumination.

The symbolism of liturgical lights: a religious and aesthetic framework to understand electricity

The use of light and darkness has a strong symbolism within the Catholic liturgy, as both elements serve a dogma in which the divine light has come to enlighten humanity. Therefore, the use of artificial lights has always been encoded. In this regard, the regulations of the Sacred Congregation of Rites – a Vatican institution created by Pope Sixtus V in the sixteenth century – provided the guidelines for their display within churches.[7] Throughout the nineteenth century, the Vatican Curia paid an increase amount of attention to the implementation of artificial illumination in religious spaces, precisely at a time when industrial lights – gas and electricity – were arriving to the urban spaces. Indeed, the most rigorous priests vehemently criticized these illumination systems for their associations, as they excessively evoked the world of industry or, even worse, theatres, cafes and the vicious urban nightlife.[8]

Therefore, the priests and the Roman Curia would maintain a delicate balance between the respect for tradition and the tolerance (even recommendation) of the electrical systems inside churches, but only in those aspects not directly related to worship and for comfort and security reasons only, particularly in the nave and other common areas. Within these spaces, the Church could respond to its eagerness to engage with modern technologies, also attracting potential believers. Nevertheless, when it came to the liturgy and rituals, gas and electricity were strictly forbidden at the end of the nineteenth century. For these purposes, and to maintain the ornaments and solemnity of the Catholic ceremony, it was only possible to use vegetable wax, fine stearin or paraffin. Moreover, beeswax and olive oil were specifically prescribed for the altars. Certainly, light regulations were stricter at the tabernacle, altarpieces, images or around the Holy Sacrament, where the flame represented Christ, the “Light of the world”.

It is true that in the 1830s and 1840s novelties were introduced, such as allowing the use of other vegetable oils at the altar and the approval of petrol in 1869. This measure, however, sparked strong controversy since petrol lamps had strong popular and domestic connotations. Most of these regulations would be reiterated in 1903 and, although several applications of electricity were possible outside the altars, these guidelines only allowed its use for strict functional purposes, banning any dramatic or profane display. Thus, electric lights should fit into pre-industrial visual cultures and, most importantly, Catholic values and practices. Notwithstanding this, electricity would be gradually accepted, tolerated and instrumentalised, even within the sacred spaces of the altars and for wider proselytist purposes.

The Spanish Catholic Church and the public display of electricity: from rejection to appropriation

There is evidence of the occasional adoption of electric lights in urban and rural churches and other religious spaces as cloisters since the mid- and late 1880s. For instance, the Basilica of El Escorial monastery (Madrid) relied on electric lights for the public commemoration of the conversion of Saint Augustine of Hippo in 1887, which amazed those contemplating these festivities. By 1891, not only the basilica, but also the monastery and the school had electric illumination. Moreover, Teodoro Rodríguez, monk and professor of mathematics and physics at the Royal School of El Escorial, would end up patenting some electric devices in the forthcoming years.[9] Furthermore, the first uses of electric lights in public religious parades could be traced back to early 1890s, as could be seen in Easter of 1892 in Cádiz (Andalusia).[10]

Surprisingly enough, however, in 1903, the Archbishop of Madrid, Victoriano Guisasola (1852–1920), banned the use of electricity inside churches – specifically on the altar – following the requirements of the Sacred Congregation of Rites. To a certain extent, this measure underscores the need to curtail an increasingly widespread practice since Guisasola’s aim was to reinforce the dignity and severity of worship to recover the Church’s prestige. A seminarian from the northern region of Asturias expressed his agreement with Guisasola’s decision in this manner:

Very well done. Electricity is a diabolical thing and should not enter places of prayer and meditation. (…) And so I like bishops: evangelically humble and austere as the apostles. As to the modernizing bishops, I do not trust them![11]

Figure 4. Victoriano Guisasola y Menéndez (1852-1920), Bishop of Madrid (1901-1904). Image source: https://www.architoledo.org/archidiocesis/episcopio/1809-2/, downloaded December 30, 2019, 0800 GMT. In the public domain.

Technical modernity divided Spanish clergy and, indeed, there is enough evidence of the progressive introduction of electric lights inside Spanish churches throughout the first decade of the twentieth century. After all, electricity had clear economic and safety advantages. However, the seeming contradiction between gradual adoption and the opposition by certain bishops demonstrates not only the lack of consensus among the Spanish priests but, most importantly, that plain, simple and linear adoption was not possible. Indeed, electric lights were at first hidden behind false candles or in indirect lighting fixtures. At any rate, and if we borrow some of the arguments coming from the “users” and “non-users” perspective in the history of technology, the Church standpoint would be rapidly transformed from an (official) “non-user” into an eager “user”. In the 1910s, electricity would even make it into the forbidden territory of the altar and religious images. A catholic journal remarked on the lavish display of light during an important commemoration in 1912 in the small town of Villaviciosa, in the northern Spanish industrial region of Asturias:

The main altar of the spacious parochial church was adorned with plenty of flowers and decorative greenery and the Excellent Majesty’s [the Virgin] effigy was illuminated with light, displaying an artistic combination of candles and electric light bulbs that poured out a cascade of light over the Patron of Spain. This table provided a surprising and evocative glimpse, which invited the prayer.[12]

Consequently, the decrees banning electric lights on altars – still current in 1911 – spoke against an ultimately unavoidable practice. Moreover, the use of bulbs, coloured lights, projectors or reflectors on altars or images would become more frequent from the 1910s onwards, even by using elements of such novelty as crowns of electric bulbs for the statues of the Virgin Mary.

Electricity reinforced the spectacular nature of Catholic worship, although not all priests and practitioners would approve. Through its instrumentalization, the Spanish Church would reinforce a Baroque religious sensibility still prevalent among the public. The survival of this aesthetic framework represented, in fact, a mismatch regarding the Roman guidelines for worship, at a time when the liturgical renewal proposed by the Vatican supported a return to medieval and monastic sobriety.

Notwithstanding this, the Spanish Catholic curia realized the potentialities of electricity for their purposes of maintaining and, if possible, increasing their social influence. Along these lines, the systematic display of electric lights in public ceremonies would become an essential feature within the Church’s power struggles over the public space. While different social and ideological actors – including public authorities or trade unions – were going out into the streets, showing their force through rallies, parades and civic festivities as that of the 1st of May, the Spanish Church quickly understood the fascination that technological innovation generated, particularly, the amazement that electric light triggered among wider audiences.

Indeed, the public affirmation of ecclesiastical authority and its visualization required a carefully planned apparatus of representation whose goal was to mobilise the senses, causing a deliberately emotional shock to attract new believers. Going back to our norther region of Asturias, the Church would rely upon the monumental use of electric lights for numerous commemorations. In 1911 during the celebration of the mystery of the Immaculate Conception in the Jesuit College of the industrial city of Gijón, the press (and not just the catholic press) praised its impressive display at the College’s courtyard and church, mesmerizing those gathered around:

By the time the celebration ended the courtyard was lavishly lit. The windows facing the garden were full of lights; the ceiling of the lower cloister was adorned with arches containing Venetian-style lanterns and in the middle of the garden stood as never before in its elevated and artistic pedestal the magnificent marble statue of our beloved Virgin, to which they gave a divine tint the grandiose electric arc lights[13].

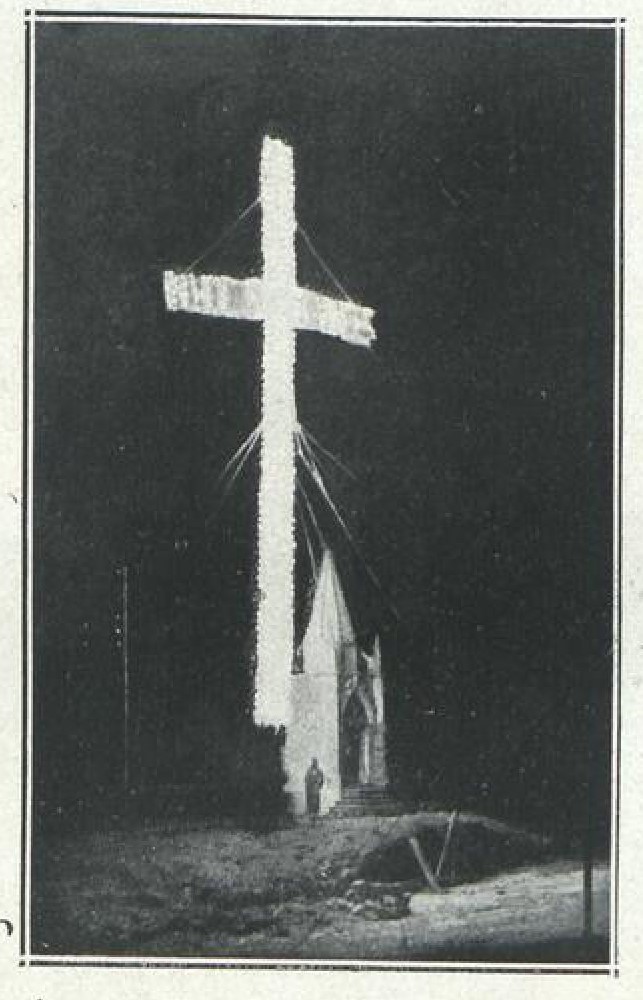

Two years later, the important Cathedral of Oviedo (capital of Asturias) was profusely illuminated during the Constantinian Festivities, even with a Cross of Angels made entirely of electric bulbs. This practice, however, was not only limited to Asturias since other spectacular uses of electric crosses could be tracked during the same festivities in Barcelona.

Figure 5. An electric cross of 2.000 bulbs. Constantinian Festivities at Barcelona (1912). Image 5 source: La Hormiga de Oro, XXIX, no. 45, (November 9th 1912): 716. Copyright expired.

One last example also comes from Asturias. In 1915, a pilgrimage to Covadonga’s sanctuary – in which even King Alfonso XIII participated –, exhibited a splendid display of electricity, and the press commented:

The cave looked fantastic, because of the myriad of polychrome electric lights decorating the side-chapel of the Virgin. The King and his entourage left the Hotel after the meal, contemplating the lighting and chatting with the aristocratic personalities that there were, (…)[14]

As electricity was incorporated into urban churches in the first decades of the twentieth century, some anti-clerical newspapers in Gijón would even complain about the skilful way in which some communities of nuns attracted high-society ladies to their chapels, luring them through exclusive and elegant services, with dazzling altars laden with flowers and electric lights.[15]

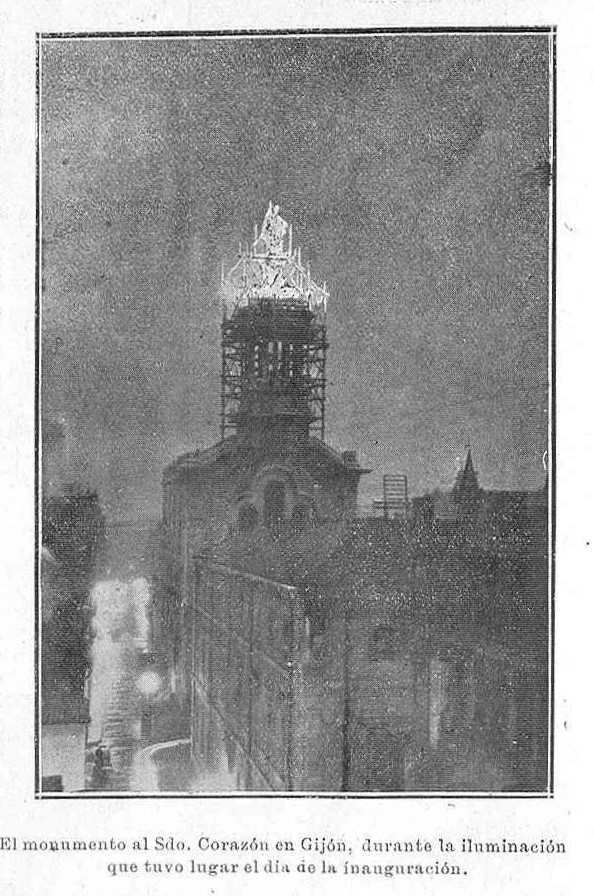

Gijón was, indeed, a deeply polarised and fragmented city, which encapsulated many of the social and political tensions that traversed Spanish society in early twentieth century.[16] Conservative sectors usually vilified the presence of a strong socialist and anarchist trade-union movement that were pushing workers away from God and Catholicism. So, within that context, electricity took part in the wider struggles over the public space already mentioned. That was particularly clear during the inauguration of the church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in 1920, which included a superb illumination in with powerful electrical spotlights of “14,000 bulbs” shone on the great statue of Christ.[17] In what would become the first “skyscraper” of the city, the image of the Sacred Hearth would stood above the city, symbolically dominating the landscape of this industrial quarters, until then dominated by the smoke and chimneys of factories.

Figure 6 and 7. A glance at the Basilica of the Sacred Hearth (Gijón, Asturias) built between 1918 – 1922. Image 6 source: https://www.iglesiadeasturias.org/parroquia/basilica-santuario-del-sagrado-corazon/ , downloaded December 30, 2019, 0800 GMT. In the public domain. Image 7 source: Páginas escolares: revista mensual. Época segunda, XVII, no. 1 (1920): 14. Copyright expired.

Electricity and religion: why aesthetics mattered.

There are two main take-home messages from this story. Firstly, we should not overlook aesthetic considerations while considering the incorporation of any technological innovation. Aesthetics mattered; in fact they mattered a great deal. In this case, the Catholic liturgy offered the aesthetic framework to interpret electricity, acting as the cultural background through which the uses of electric lights were understood, mobilized and eventually shaped. Far from the linear adoption of a brand-new and superior technology, the electrical modernity was not celebrated at first, but tamed to fit the visual cultures connected to the values of the Church. However, electricity and its own characteristics would implement a neo-baroque aesthetic that contributed to the Church’s power struggles in the public sphere. Therefore, aesthetics explorations open a fruitful ground to understand the dynamics of innovation, adaptation and rejection of new technologies and their overlap with wider political and societal issues.

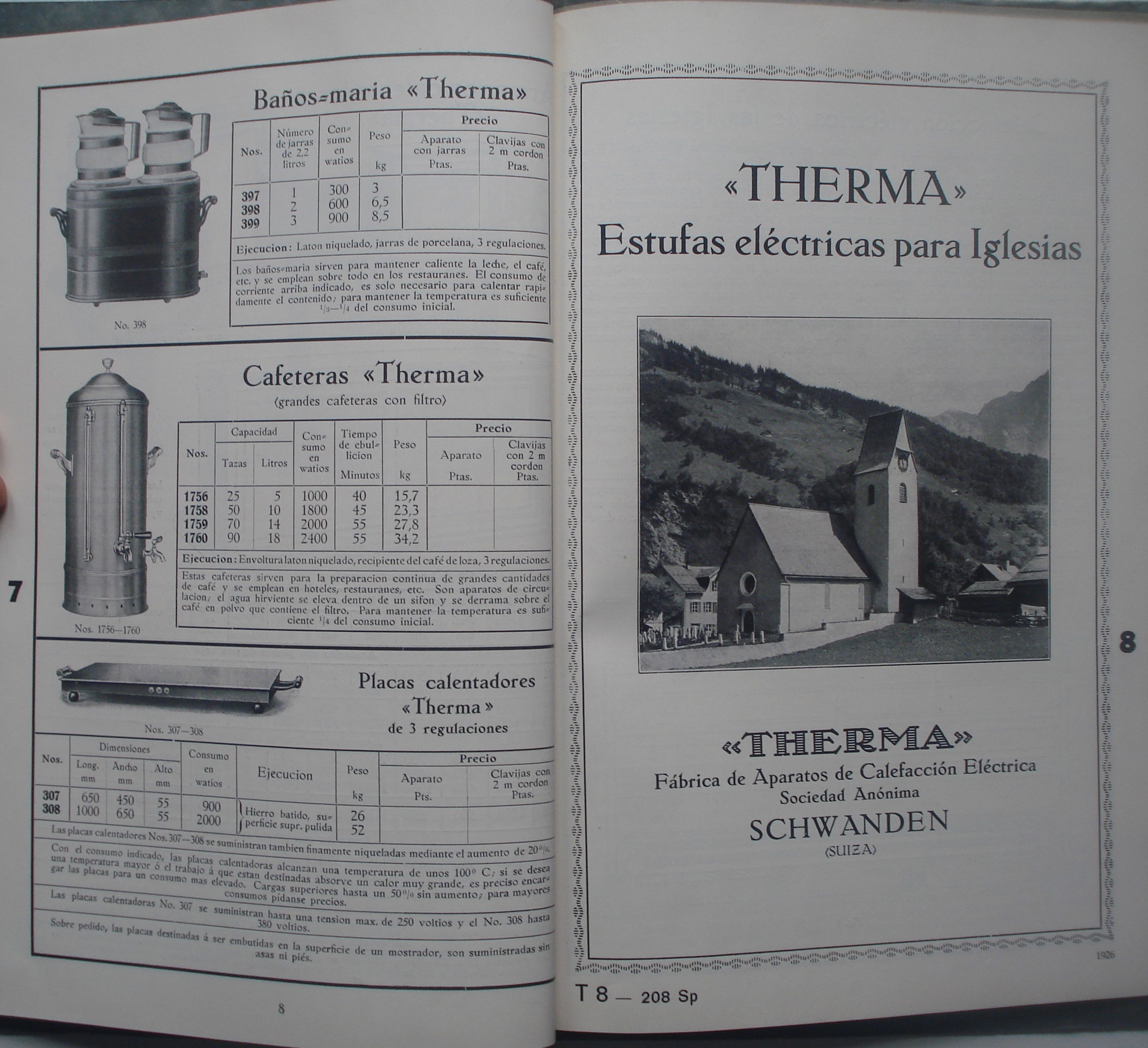

Secondly, we should consider the role that religious beliefs and practices play in influencing public attitudes towards technological innovation, even mobilizing wider needs and desires. This includes the effect that religious communities can have on individual and collective choices and the impact of these attitudes and use patterns on the subsequent development of technology. In this case, we can ask whether the Church’s display of electricity – both in churches and in other public ceremonies – could have significantly affected domestic practices in early twentieth century Spain. Since most Spanish households lacked electric lights and other elements such as electric heating, churches were a good place to contemplate innovation, familiarizing believers with notions of modern comfort, disseminating positive images of these technologies and, ultimately, urging their transfer into other settings. In fact, electricity and other technologies would end up modifying the traditional meaning – even the architecture – of modern churches, which would shift from symbolism to functionality.

Figure 8. Electric heating for churches. Special section in the THERMA supplier’s catalogue (Barcelona, 1924). Museo del Pueblo de Asturias. Catálogo THERMA, Fábrica de Aparatos de Calefacción Eléctrica Sociedad Anónima, Schwanden (Suiza). Representantes exclusivos para España Domínquez y Serra en Comandita. Barcelona. [s.l.]: [s.n.], Copyright expired.

Copyright 2020 by Daniel Pérez Zapico

Dr Daniel Pérez Zapico is a Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Leeds. His research interests are related to cultural approaches to the histories of electricity and electrification.

Suggested Readings.

- Michel Lagrée, La bénédiction de Prométhée: religion et technologie (Paris: Fayard, 1999).

- Mark J. Sussman, Staging Technology: Electricity and the Magic of Modernity (New York: New York University Press, 2000).

- Wolfram Kaiser and Christopher F. Clark, eds. Culture wars: Secular-Catholic Conflict in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Catherine Vincent, Fiat Lux. Lumière et luminaires dans la vie religieuse en Occident du XIIIe siècle au debut du XVIe siécle (Paris: Les éditions du Cerf, 2004).

- Don O’Leary, Roman Catholicism and Modern Science: A History, (London : Continuum, 2006).

- Colette Apelian, ‘Modern mosque Lamps: Electricity in the Historic Monuments and TouristA of French Colonial Fez, Morocco (1925-1950)’, History and Technology, 28:2 (2012): 177-207.

- Jeremy Stolow, ed. Deus in Machina: Religion, Technology, and the Things in Between (New York: Fordham University Press, 2013).

Notes.

[1] See Geoffrey Cantor and John Hedley Brooke, Reconstructing Nature: The Engagement of Science and Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000); Thomas Dixon, ed. Science and Religion: New Historical Perspectives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010); Jeremy Stolow, ed. Deus in Machina: Religion, Technology, and the Things in Between (New York: Fordham University Press, 2013).

[2] Jean Séguy, ‘Introduction: The Modern in Religion’, Social Compass, 36:1 (1989): 3–12.

[3] See Michel Lagrée, La bénédiction de Prométhée: religion et technologie (Paris: Fayard, 1999).

[4] For instance, Botti’s thesis on the Spanish national Catholicism emphasises the compatibility between reactionary political discourses and modern capitalist economic practices. See Alfonso Botti, Cielo y dinero. El nacionalcatolicismo en España (1881-1975) (Madrid: Alianza, 1992).

[5] William J. Callahan, The Catholic Church in Spain, 1875-1998 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2000).

[6] Nestor Herrán, ‘“Science to the Glory of God.” The Popular Science Magazine Ibérica and Its Coverage of Radioactivity, 1914-1936’, Science and Education, 21 (2012): 335-353; Jaime Navarro, ‘Promising redemption. Science at the service of secular and religious agendas’, Centaurus 59:3 (2017): 173-188.

[7] Catherine Vincent, Fiat Lux. Lumière et luminaires dans la vie religieuse en Occident du XIIIe siècle au debut du XVIe siécle (Paris: Les éditions du Cerf, 2004).

[8] One of rhetorical strategies frequently used by Catholic advocators, at the turn of the nineteenth century, consisted in contrasting the simplicity and purity of the pre-industrial world with the urban settings. There, modern times were commonly depicted through dark attributes, alluding to a kind of “moral night” where, despite all the technological advancements, God and faith remained the true undisputed lights: “on the moral night we are plunged, and whose darkness neither gas nor electricity could vanquish, the beacon to which humanity’s restless gaze is directed still is the Christian idea.” El amigo del pobre: publicación quincenal, X, no. 331, (November 1st 1915): 4.

[9] La Ilustración Católica. Seminario religioso científico-artístico-literario, May 15, 1887, 157; June 30, 1891, 186-187. La Hormiga de Oro, February 16, 1892, 72

[10] La Ilustración Católica. Revista de literatura, ciencia y arte cristiano, April 30, 1892, p. 114.

[11] El progreso de Asturias, October 24, 1904, p. 3

[12] El Principado, December 08, 1912, p. 3

[13] Páginas escolares: revista mensual, Año VII, no. 81 (1911): 585-587.

[14] El Pueblo Astur, August 31, 1915, p. 15.

[15] El Noroeste, October 26, 1904, p. 5.

[16] See Pamela Radcliff, From Mobilization to Civil War: The Politics of Polarization in the Spanish City of Gijon, 1900-1937 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

[17] Páginas escolares: revista mensual. Época segunda, Año XVII, no. 1 (1920): 14.