Visualizing Imprudentes: Technology and Consumption in Turn-of-the-century Mexico City

Technology’s Stories v. 8, no. 2 – DOI: 10.15763/jou.ts.2020.09.28.06

Montano_Visuaizing Imprudentes

Jacinto S. García arrived to Mexico City in the summer of 1909. Astonished to find a “beautiful, clean, grand and Europeanized city,” the business representative of the Argentine government judged it deserved to be listed among the urban centers of the civilized world.[1] Throughout the route, he noted, there were “no longer any Teocallis, or Aztec pyramids, or any remains of the ancient Toltec or Maya civilizations!” Beautiful and animated streets greeted him instead. Unfolding before his eyes were streets, “lively as those of Madrid, urban as those of Vienna, and populous as those of New York.” Their cosmopolitan air was completed by “smooth cement sidewalks, impeccably paved streets, and superb electric streetcars full of passengers,” elements which along with “hundreds of luxury rental carriages, and thousands of automobiles formed the concert of modern civilization and the backbone of human activity.”[2]

García described a thriving metropolis with all the accouterments of turn-of-the-century urban modern life that capitalinos (Mexico City residents) would have loved to read. Political stability, substantial foreign investments, and the consolidation of an export-based economy and light manufacturing evinced President Porfirio Díaz regime’s mantra of order and progress. As the jewel of the administration’s modernization drive, the capital underwent numerous sanitation and beautification projects in the face of rapid population growth and early industrialization. While its population of 250,000 in 1880 almost doubled by 1910, the urban footprint quintuplicated from 5.28 to 25.15 square miles in 1910. Neither uniform nor following informed plans, this expansion resulted in an overcrowded downtown area and low-density sprawled marginal settlements. In this context, capitalinos welcomed faster and reliable transportation.

Mexico City’s transformation was neither absolute nor without glitches. Introduced at the turn of the century, eléctricos (electric streetcars) not only stood as tangible proof of the city’s technification but were also the source of interruptions to the concert of modern civilization: accidents. Street accidents were, in part, a consequence of the conflation of new modes of transportation (bicycles, tramways, carriages, and automobiles), higher traveling speeds, and increased traffic in urban centers across the globe. Nevertheless, accidents were also the result of battles over urban space, over who and what belonged on the streets. In other words, to whom did the street belong?

As momentary interruptions of social life, accidents offer snapshots of a society. Accidents revealed the dark side of technification, which generated much discussion of their causes, experiences, and possible solutions. Thus, technical mishaps allow historians to gauge not only how a specific device was experienced but also how technology users were imagined. Historian David Nye proposed that to understand a particular machine’s history, one must look at its social reality.[3] He invited us to move beyond the study of material objects towards the study of their use as a functional device and how collective human experience shaped its meaning.4 Moving the conversation away from the objects themselves, David Arnold argued that technological innovations since the late 19th century transformed our conceptualizations of time and space, body, self, and “other.”[4] Eléctricos’ altered each of these.

Textual and visual commentary of streetcar accidents serves as a lens to examine a society’s values and anxieties. As events that brought the city’s rhythm to a halt, even if momentarily, accidents generated a wealth of primary sources. Diverse outlets from newspapers, medical journals, police reports, and court records to popular songs registered these. While doctors diagnosed and treated bodily injuries and inventors worked to design devices to prevent and reduce bodily harm, municipal authorities looked increasingly into traffic regulations. Social critics, lithographers, and wordsmiths also joined the conversation. Looking at these, we come across the values, anxieties, fears, and hopes of a particular society at a given point in time. Visual representations of accidents were captured in historietas (advertising comic strips), broadsides, and exvotos.[5] The following discussion focuses on the first.

Historietas

Accidents brought to the fore the relationship between bodies and machines in public spaces. How capitalinos discussed, accidents reveal whom they imagined were to be the ideal users. As soon as the announcement of the plan to electrify the city’s tramways became public, newspapers set out to debate what faster transportation meant for the city. Their assessments were full of hopes and anxieties. Although the arrival of the eléctricos meant another step in the capital’s material progress, they expected that accidents would claim many pellejos (lives).[6] Assigning prime responsibility to undisciplined users (drivers and riders) and non-users (pedestrians/bystanders) who made poor choices worked to normalize accidents. Textually this was done through the label of imprudentes (imprudent individuals) who committed imprudencias (imprudent actions).[7] A report titled “Imprudencias,” published a few months from the eléctricos’ inauguration, cited the public’s carelessness as a significant tragedy.[8] This discussion concentrates on how ideal users, that is disciplined users who did not cause accidents, were imagined. This imagining occurred both textually and visually in the city’s newspapers, penny press, broadsheets, and advertisements. The leading cigarette manufacturer El Buen Tono repeatedly and creatively integrated accidents in their ads. The company enjoyed a strong record of incorporating the latest innovations in advertising. If tobacco companies were at the forefront of making a spectacle of city life and creating an urban mass culture, El Buen Tono distinguished itself from competitors for their public displays and widespread use of lithography.[9] It established its lithograph shop, an achievement few others could replicate, to print packs, labels, wrappers, posters, flyers, and, beginning in 1904, cartoon strips.[10]

First, a word on historietas. Historian Thelma Camacho Morfín entertains that in the absence of signatures, it is best to consider that teamwork prevailed at the shop. One prominent team member was Juan B. Urrutia, who joined the shop as a drawing artist and lithographer in 1899, later climbing to second-in-command until he died in 1938. Urrutia was part of the team that laid out the general argument and design of the historietas below. He was a staunch urbanite whose work consistently ridiculed recently arrived peasant migrants and questioned technological innovations and scientific discoveries.[11] Much material came from his daily readings of nota roja (journalism devoted to stories dealing with physical violence related to crime, accidents, and natural disasters). The stories of the early historietas were straightforward: love stories, streetcar accidents, provincials in the city, and health, among others.[12] Camacho Morfín argues these showed Urrutia’s “rejection of technology: [in which] all means of communication failed, were destroyed or dangerous to city residents.” In the case of streetcar accidents, I find not a rejection of the technology per se, but rather the effort to ridicule ill-fitted users. In doing so, these historietas assisted the disciplining of users/non-users carried out in contemporary outlets by providing a visual language.

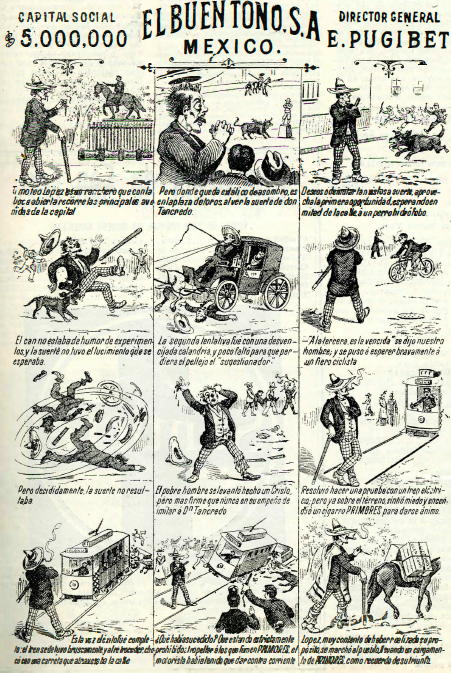

Figure 1. El Mundo Ilustrado, 24 July 1904, Hemeroteca Nacional Digital de Mexico.

The first historieta that dealt with streetcars follows the adventures of rancher Timoteo López in his visit to the city.[13] (Fig. 1) As a provincial, the character is an outsider, uneducated in the modern civilization’s concert on the streets. The famous equestrian statue of Charles IV of Spain in the first panel squarely sets the story. López traverses the streets open-mouthed. We next find him ecstatic at the bullring. The bullfighter’s feat left such an impression that he sets out to replicate it. The third panel depicts him in the middle of the street, awaiting a rabid dog. His stance appears nonsensical as a group of men with clubs in hand follows the animal. The next panel shows López at mid-air with the dog’s teeth sinking into his buttocks. Panels five and six show his attempts with a rickety calandria (carriage) and a furious cyclist. Despite the awful results, López decides to try an eléctrico. Once on the tracks, he feels scared. He goes on to light a PRIMORES cigarette to gain strength. The approaching eléctrico with a trail of destruction behind it (including a horse, a carriage, and individuals) comes to an abrupt stop. Those witnessing the eminent accident were astounded. What had happened? Drivers were strictly prohibited from striking smokers of PRIMORES cigarettes according to the caption. Thus, the driver energetically applied contracorriente (countercurrent braking system). Satisfied, López sets out for his village with a box of the cigarettes fastened to a mule as a reminder.

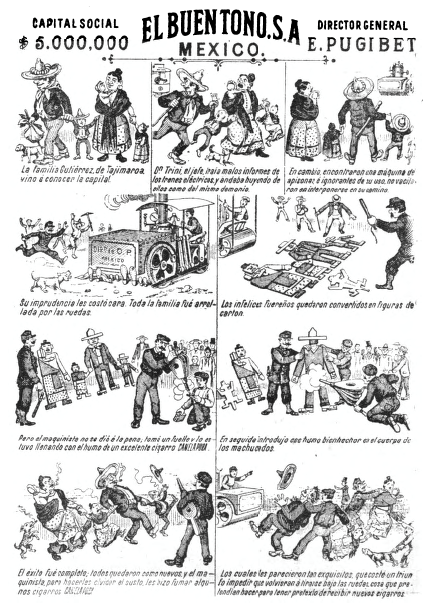

The historieta chronicling the Gutiérrez de Tajimaroa family’s visit echoes elements of the López’s story.[14] (Fig. 2) Depicted in full archetypical attire of provincials (men in cowboy garb and the high-crowned, wide-brimmed hat associated with the popular classes, and women in floor-length floral print skirts and rebozos (shawls)), the family flees at the sight of a streetcar. The patriarch Don Trini had been “ill-informed” about eléctricos and thus ran away as if they were the devil himself. Contrastingly, when the family eyes a steamroller, they stand on its path intrigued. They paid a heavy price for their imprudencia (carelessness) as the entire family is left flat as carton figures. The driver promptly fills a bellows with smoke from a CANELA PURA cigarette and introduces it into the bodies of machucados (knocked down individuals). The technique is a total success; the driver brings the family back to life. The driver has them smoke more cigarettes to forget the susto (fright). Their excellent taste was counterproductive as they kept trying to be knocked down once again to enjoy more cigarettes.

Figure 2. El Mundo Ilustrado, 9 Oct. 1904, Hemeroteca Nacional Digital de Mexico.

Technology in the city offered thrills and chills. Increased traffic and the sight of unusual machinery on the streets placed increasing demands on bodies. Individuals encountered danger at factories with the introduction of new machinery and fuels. López and the Gutiérrez de Tajimaroa were briefly in the city; their trip was a pleasure trip, unlike the thousands negatively affected by Porfirian policies and forced to migrate to the capital. Nonetheless, their encounters with modern technologies placed demands on their bodies. Provincials are maladjusted to their surroundings in both historietas. By the late 19th century, the ability to assess danger was considered a rational act; those unable to were, by extension, irrational, backward, and unfit for urban life. The capacity of an individual to be alert, to pay attention had become the subject of study. Art critic Jonathan Crary argues that the problem of attention developed within “an emergent economic system that demanded attentiveness of a subject in a wide range of new productive and spectacular tasks.”[15] This new model of behavior “was articulated in terms of socially determined norms and was part of the formation of a modern technological milieu.”

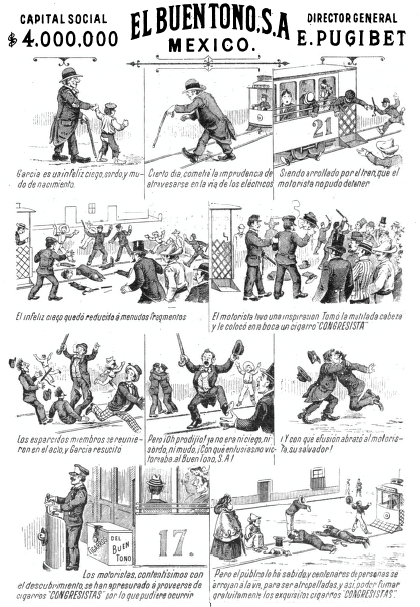

Figure 3. El Mundo Ilustrado, 14 Aug. 1904, Hemeroteca Nacional Digital de Mexico.

Accidental injury and death were not safe from comical renditions. Porfirian wordsmiths and lithographers as heirs of a robust satiric press and rich graphic tradition imbued humor negro (gallows humor) in their coverage of the capital’s physical transformation and its glitches.[16] Mexicans nurtured “a fondness for lurid descriptions of mangled bodies and monstrous technologies,” joining the morbid fascination with violence, the suddenness, and randomness of accidental deaths common on the streets of New York and Paris.[17] Ben Singer contends that newspapers gave meticulous attention to the physical intricacies of such deaths not only because grotesque sensationalism sold copies but also due to a “distinctive hyperconsciousness of environmental stress and physical vulnerability in the modern city.”[18]

The modern city placed increasing demands on the senses, and to the body. In some instances, the inability or unwillingness to respond accordingly was questioned as unnatural, irrational, and, thereby, resulted in accidents interpreted as a natural consequence. A third historieta elucidates this. García, a deaf, blind, and mute, replaces the provincial as the protagonist.[19] (Fig. 3) In the second panel, he crosses the tracks as an eléctrico approaches. An imprudencia, the caption notes, that “left him in pieces.” Amid the chaos, the driver places a CONGRESISTAS cigarette in the decapitated head’s mouth. Instantly, the scattered limbs come together. García resurrects neither blind nor deaf-mute. The penultimate panel depicts a driver with a wooden box behind him labeled “El Buen Tono Cigarettes,” with the caption: Thrilled with the breakthrough, tram drivers hurriedly stocked up. The last panel shows an approaching eléctrico and individuals and a dog on the rails willing to be knocked down in hopes of smoking cigarettes free of charge.

Conclusion

Historietas ridiculed the imprudentes’ lack of modern instincts through local lore and common visual references. These characters’ inability to move around streetcars carefully inversely exemplified the values and characteristics of ideal users: prudence, alertness, attention, and bodily discipline.[20] More importantly, the ideal user or non-user of streetcars in the case of pedestrians/bystanders was to abstain from invading the machine’s right of way. The issue at hand was not seen as a dispute over space, over who has the right to occupy the street, but rather the acquiescence that streetcars had won the right of way over all other vehicles and pedestrians alike.

Besides stereotyping machucados as uncultured, these characters are ill-prepared to traverse streets civilly. López embodied lower-class manliness as instead of assessing danger, he used the opportunity to prove his valor. Despite being mesmerized by what he finds in the capital, López is obsessed with mimicking the bullfighter to prove his manhood, mirroring the unrefined manliness of imprudentes. Hombres del pueblo (lower-class men) allegedly shared a desire to prove their valor by dodging cars, zigzagging coaches, and eléctricos. They would also hesitate to avoid an accident just to capture people’s attention on the streets. The newspaper El Imparcial argued that the reformation of those habits would “reduce accidents and many other males (wrongs).”[21] Unrefined manliness also ran against the ideal modern male who controlled his needs, instincts, and emotions, and was moderate in the manner of speech, dress, and dining.[22] Giving free rein to one’s emotions and instincts was considered typical of the less instructed. Although etiquette manuals such as that of Manuel Antonio Carreño underlined self-control, more consequently was how such a view colored the penal code. For instance, the latter showed higher tolerance towards individuals who resolved conflicts in a rational way (dueling) than those who did so in an impulsive manner (street fight).[23]

These historietas exculpated eléctricos by reinforcing the narrative of imprudentes and selling a ticket to modern civilization’s concert: consumption. First, machucados characterized as either provincial (and thus uncultured to the technological transformation the city had undergone and generally afraid of technology) or disabled were unprepared to dodge dangers on the streets.[24] Secondly, cigarettes worked to prepare or “regenerate” individuals for modern living. López smokes to gain valor, while others benefit from their regenerative value. In all cases, it is the consumption of cigarettes that saves them. Smoking transformed bodies. After all, the machine-rolled cigarette was the Porfirian symbol par excellence of modernity. Through smoking, individuals acquired a feature of capitalinos, that of a consumer.[25]

Undisciplined bodies had no place in the concert playing on the streets. Far from the work of unruly machines, accidents were a consequence of accident-prone individuals. This view echoed the work of a generation of technocrats and professionals (e.g., doctors, hygienists, and criminologists) who found in the bodies and behavior of the lower and popular classes the root cause of a plethora of social problems.[26] Social commenters deemed there was no time to extirpate the source of machucamientos (accidents). As El Imparcial assessed early on, the country’s material progress “ran at a greater speed than our people’s education.”[27] Imagining machucados as both lower-class and responsible for their “ill-faith” did more than ridicule and further stereotype provincials and poor individuals in the city, coloring the authorities’ responses and public outcry for many years.

Diana J. Montaño is assistant professor of History at Washington University in St. Louis. Her forthcoming book Electrifying Mexico: Technology and the Transformation of a Modern City (University of Texas Press, 2021) delves into how ordinary citizens (businessmen, inventors, doctors, housewives, maids, domestic advisors, and electrical workers among others) saw themselves and their city as modern through electricity and how they became “electrifying agents” first crafting a discourse for an electrified future and secondly, by shaping its consumption. Taking a user-based perspective, it reconstructs how electricity was lived, consumed, rejected, and shaped in everyday life. Her article “Ladrones de Luz: Policing Electricity in Mexico City, 1901–1918” will appear in the HAHR 101.1 issue next February.

Copyright 2020 Diana Montano

Endnotes

[1] Jacinto S. García. Memorias íntimas de México: a propósito de la revolución Mexicana. Lima: Fondo Editorial Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 2005, 24-25.

[2]” Ibid.

[3] David Nye, Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880-1940. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992, ix.

[4] David Arnold, Everyday Technology: Machines and the Making of India’s Modernity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013, 69.

[5] A votive offering to a saint in gratitude for a miracle received. In Mexico, votive paintings on metal sheets usually depict the petitioner, the saint’s figure, and a brief description of the miracle.

[6] El Universal, 16 January 1900.

[7] For the social reconstruction of American streets with the arrival of automobiles see Peter D. Norton, “Street Rivals: Jaywalking and the Invention of the Motor Age Street,” Technology and Culture 48:2 (Apr. 2007): 331-359; for the street as a site for disciplining efforts and contestation see David Arnold, “The Problem of Traffic: The street-life of modernity in late-colonial India,” Modern Asian Studies 46:1 (2012): 119-141.

[8] El País, 17 April 1900.

[9] For advertising technology, see Steve Bunker, Creating Mexican Consumer Culture in the Age of Porfirio Diaz. Albuquerque: The University of New Mexico Press, 2012, 30-48.

[10] For industrial lithography, see Thelma Camacho Morfin, Las historietas del Buen Tono (1904-1922): La litografía al servicio de la industria. Mexico: UNAM, 2013.

[11] Ibid, 65-55.

[12] Ibid, 79-80.

[13] El Mundo Ilustrado, 24 July 1904.

[14] El Mundo Ilustrado, 9 October 1904.

[15] Jonathan Crary, Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture. Cambridge: MIT, 2001, 29-30.

[16] For the satiric press/political cartoon see Maria Elena Díaz, “The Satiric Press for Workers in Mexico, 1900-1910: A Case Study in the Politicisation of Popular Culture,” Journal of Latin American Studies 22:3 (1990), 497-526; Fausta Gantús, “La ciudad de la gente común. La cuestión social en la caricatura de la Ciudad de México a través de la mirada de dos periódicos: 1883-1896,” Historia Mexicana 59:4 (2010): 1247-1294.

[17] Diana J. Montaño, “Machucados and Salvavidas: Patented humor in the technified spaces of everyday life in Mexico City, 1900-1910,” History of Technology Vol. 34 (2019): 43-64. https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/book/history-of-technology-volume-volume-34-2019-special-issue-history-of-technology-in-latin-america/machucados-and-salvavidas-patented-humour-in-the-technified-spaces-of-everyday-life-in-mexico-city-1900-1910

[18] Ben Singer, Melodrama and Modernity: Sensational Cinema and Its Contexts. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001, 74. For Paris, see Gregory Shaya, ¨Mayhem for moderns: the culture of sensationalism in France, c. 1900,” Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 2000; for sensational reporting and suicide in Mexico City, see Kathryn Sloan, Death in the City: Suicide and the Social Imaginary in Modern Mexico. Oakland: University of California Press, 2017.

[19] El Mundo Ilustrado, 14 August 1904.

[20] For the theme of alertness among American cartoonists, see, Scott Bukatman, The Poetics of Slumberland: Animated Spirits and the Animating Spirit. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2012).

[21] El Imparcial, 7 August 1901.

[22] Elisa Speckman, “Las tablas de la ley en la era de la modernidad,” in Claudia Agostoni and Elisa Speckman Guerra, eds., Modernidad, alteridad y tradición: la ciudad de México en el cambio de siglo (XIX-XX). Mexico: UNAM, 2001, 253.

[23] Ibid, 253-254.

[24] For rural society and technology see William H. Beezley, Judas in the Jockey Club and Other Episodes of Porfirian Mexico. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1987, 67-88.

[25] Bunker, Creating Mexican Consumer Culture, 44-45.

[26] For the transformation of the working class into valued citizens, see Robert M. Buffington, A Sentimental Education for the Working Man: The Mexico City Penny Press, 1900-1910. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015; on doctors and hygienists see Claudia Agostoni, Monuments of Progress: Modernization and Public Health in Mexico City, 1876-1910. Mexico: UNAM, 2003; on criminology see, Pablo Piccato, City of Suspects: Crime in Mexico City, 1900-1931. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001.

[27] El Imparcial, 3 October 1900.