Speed Bugs: American Motorsports and the Pursuit of Speed, 1926-1932

Technology’s Stories vol. 3, no. 2 – doi: 10.15763/JOU.TS.2015.9.1.07

Speed and Risk in American Entertainment [1]

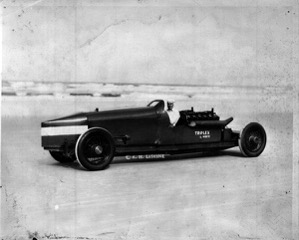

World War I flying ace and racecar driver, Eddie Rickenbacker told readers of the Altoona Tribune that the greatest accomplishment of the 1928 racing season “was the bringing back to America of the automobile speed supremacy of the world.”[2] In April 1928, Philadelphia-native, Ray Keech, reclaimed the World’s Land Speed Record from English driver, Malcolm Campbell (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ray Keech

Keech traveled at an average speed of 207.55 miles per hour racing on the packed sand of Daytona Beach, Florida. Americans, such as Eddie Rickenbacker, perceived international speed records and automobile races as important symbols of modernity and progress, during the first decades of the twentieth century.[3] Racing enthusiasts celebrated the technical accomplishments of multi-faceted drivers, such as Ray Keech, who raced against the clock on straightaway courses and vied for gold and glory against the nation’s best drivers on oval tracks located across the United States. Like many other racecar drivers of the period, Ray Keech paid the ultimate price for his pursuit of speed. Two weeks after winning the 1929 Indianapolis 500, Keech crashed to his death on the Altoona, Pennsylvania board track at the age of twenty-nine. Keech’s wife, Sarah, witnessed her husband’s fatal accident from the grandstand, and through tears she commented to the crowd of newspapermen, “It’s all part of the racing game.”[4]

This essay traces the racing careers of Ray Keech and his contemporaries to examine the ways Americans conceptualized speed and risk during the 1920s and 1930s. Racecar drivers craved extreme thrills behind the wheel of their purpose-built racecars. They willingly risked their own physical safety to set new speed records, push the boundaries of automobile technology, and entertain spectators. Drivers took great pride in their ability to set up and skillfully operate their unpredictable and failure-prone racecars at the speedway. When drivers walked away from the mangled remains of their racecars after spectacular, high-speed crashes, Americans reaffirmed their belief in the ability of human beings to maintain control over an increasingly machine-ridden and fast-paced society. Drivers did, however, recognize the tenuous relationship between men, machines, and environment. Racecar drivers engaged in a variety of rituals and superstitions surrounding speed contests believing that fate could intervene at any moment. When men did lose their lives in the pursuit of speed, their fellow drivers and spectators, such as the resilient Mrs. Keech, rationalized auto racing fatalities as an unfortunate, yet unavoidable, consequence of modern life.[5]

A Need for Speed

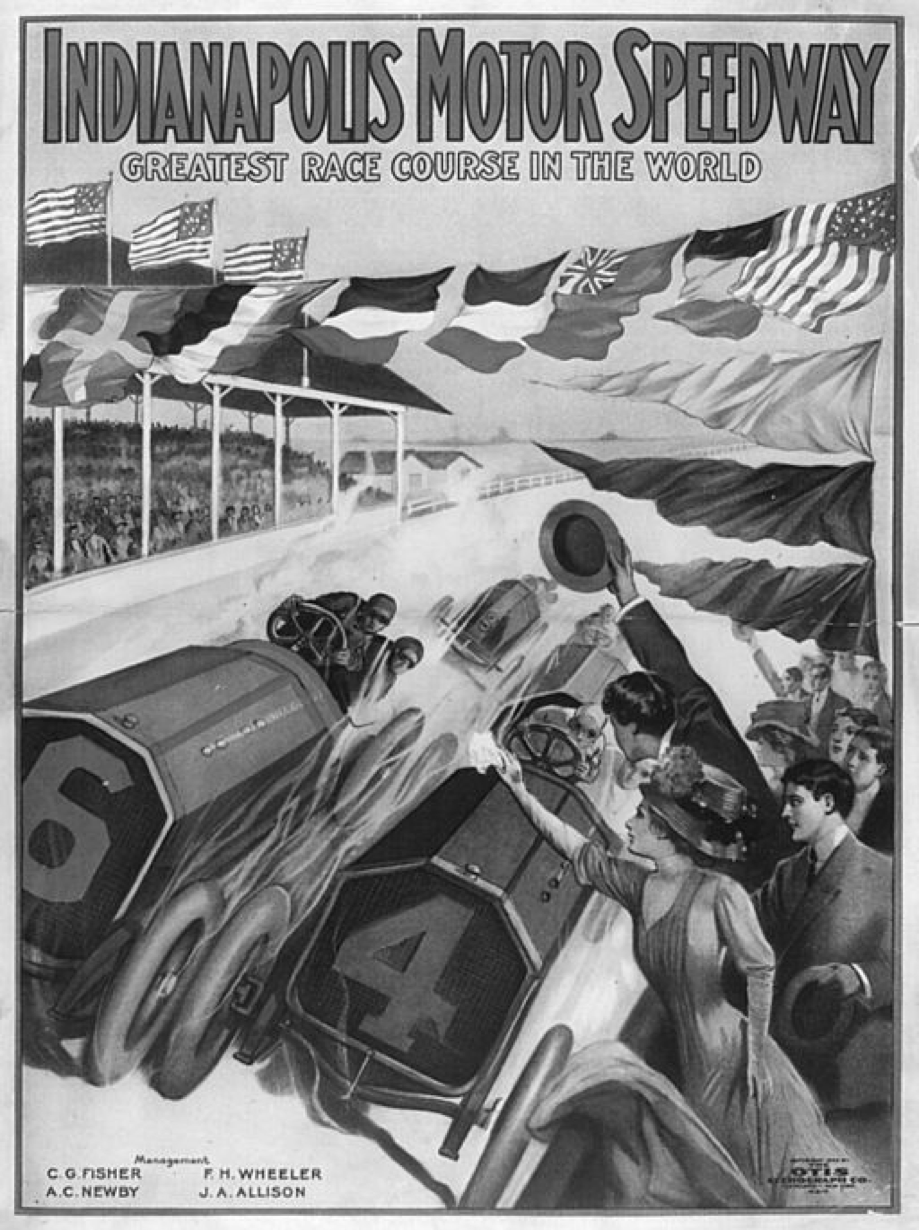

Americans had been discussing the multi-sensory experience of speed, since the advent of the railroad in the nineteenth century. Traveling at speeds significantly faster than horse-drawn carriages, early railroad passengers described how the landscape outside of their train window blurred beyond recognition at high speeds. Victorian railroad passengers had been unsettled by the distortion of scenery into blocks of colors and shapes from their seats in the train.[6] By the late 1920s, Americans had become accustomed to traveling at higher speeds in trains and automobiles. Fascination with speed bled into popular amusements, such as automobile races, where people paid admission to participate in a heightened sensory experience.[7] The men and women who filled the grandstands of the nation’s speedways watched the brightly-painted racecars blur into bands of color at high speeds, smelled the engine exhaust, and listened to the choir of whining engines (Figure 2).[8]

Figure 2: Racing Poster – Indianapolis Motor Speedway

This multi-sensory experience of speed at a racetrack created an emotional response that many Americans could not achieve driving their passenger automobiles on country roads and urban intersections.

For racing insiders, the need for speed was one of many factors motivating their participation in motorsports. Drivers and racing officials viewed technological progress and rational control over the material world as the essence of modernity. They argued that organized speed contests had important technical implications beyond simply being a leisure activity that fascinated the masses. Members of the American Automobile Association’s (AAA) Contest Board, the major sanctioning body of speed contests within the United States, argued that automobile racers knowingly risked their personal safety on the speedway in order to improve passenger automobile technology. AAA official and veteran racecar driver, L.J. Bergere explained, “Racing has done far more than any other factor to provide the laboratory, the crucible out of which has emerged the handsome speedy, relatively simple and mechanically marvelous motor car of today.”[9] Members of the Contest Board and professional racecar drivers viewed motorsports as a scientific undertaking. They consistently argued that racecar drivers competed in physically grueling, high-speed endurance races in order to test automotive products and improve the overall safety of passenger vehicles for consumers.

In addition to competing in organized racing events, several drivers tested their personal merits against the clock attempting to gain international recognition by adding their names to the World’s Land Speed Record books. When Barney Oldfield travelled at a record breaking 131.72 miles per hour in 1910, he told reporters that “A speed of 131 miles an hour is as near to the absolute limit of speed as humanity will ever travel.”[10] Less than twenty years later, however, racecar drivers were on the brink of traveling at 200 miles per hour. Inquisitive engineers and racecar builders had pushed the barrier of speed beyond what Oldfield imagined possible in less than two decades. Land speed trials offered racing enthusiasts the opportunity to reach speeds on straightaway courses, such as Daytona Beach, that drivers could not achieve on enclosed speedways. During the late 1920s, Major Segrave, Ray Keech, Frank Lockhart and other men were attempting to reach speeds on land that, up until then, only a small number of pilots had been able to achieve in their airplanes.[11]

Drivers participated in speed trials for several reasons. Each man wanted to see if he could push the boundaries of speed beyond that of his contemporaries. Additionally, racing enthusiasts received thrills traveling at high speeds. They also competed in speed trials for the prestige of having their names associated with the technological advancement of modern life.[12] English racing enthusiast, Major H.O.D. Segrave became the first man to travel over 200 mph in 1927 during the international speed trials held at Daytona Beach, Florida. In his autobiography, Segrave mused, “There is – for some psychological reason which I am quite incapable of analyzing – a certain thrill in the element of speed.”[13] He recalled how traveling at such speeds had warped his sense of time and space, and Segrave admitted that even the slightest bump in the sand or minute steering adjustment could have resulted in catastrophe during his record-setting speed runs.[14]

Risking It All

Much to the dismay of AAA officials, the public’s fascination with accidents and racing fatalities often superseded racecar drivers’ accomplishment in the press’ coverage of the sport. The news that Ray Keech had set a new international speed record behind the wheel of the White Triplex owned by Philadelphia construction contractor, Jim White, on April 22, 1928 was quickly overshadowed by Frank Lockhart’s fatal accident at Daytona Beach only three days later (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The White Triplex

Lockhart’s Stutz Blackhawk blew a rear tire during a speed trial causing him to lose control of his car, and Lockhart somersaulted down the beach to his death.[15] People across the world soon experienced this traumatic crash through newspaper reports, photographs, and film footage that captured Lockhart’s fatal accident http://www.britishpathe.com/video/a-tragedy-of-speed/query/Frank+Lockhart.[16] AAA Contest Board officials lamented the fact that newspapers “play[ed] up” automobile racing fatalities.[17] Members of the media and racing insiders clashed over the attraction of the sport. While some morbidly curious Americans may have attended automobile races to see accidents, racing enthusiasts argued that competitive racing, new fast times, and automotive engineering were the real attractions of motorsports.

As they debated the role of accidents within automobile racing, members of the press and racing insiders also discussed whether men, machines, or fate were to blame for speedway fatalities. Journalists emphasized that Lockhart was not at fault for his fatal crash at Daytona.[18] They argued that Lockhart, like so many other Americans during the early twentieth-century, lost his life from the result of an unavoidable technical malfunction – a flat tire. From their own experience riding in passenger automobiles, early twentieth-century Americans knew that cars were prone to mechanical failures, and they recognized that high speeds often increased the severity of automobile accidents.[19] Despite increased efforts to improve the safety features of machines, such as racecars, Americans resigned themselves to the fact that the risks of operating machines at high speeds could never be completely eliminated.[20]

Knowing the unpredictability of their machines, racecar drivers emphasized that it took training and skill to control their racecars at such high speeds. Operating technologically-complex racecars required a mixture of skill, physical strength, and experience. Racecar drivers often underwent a period of mentorship with older, experienced drivers to learn how to deftly operate their racing machines on the speedway. Drivers raced on a variety of track surfaces, including dirt, bricks, sand, and boards. Each racetrack offered a new set of challenges to drivers who learned how to successfully navigate each speedway from a combination of practice, natural talent, and mentorship. When discussing his successful land speed trial runs at Daytona Beach, Ray Keech told reporters, “Speed is a trade, just like carpentering or plumbing. You are not qualified as an expert unless you have experience.”[21] Inexperienced and reckless drivers had the potential to cause injury to themselves as well as their competitors, and racecar drivers faulted driver inexperience as an unfortunate cause of some speedway accidents.[22] Racecar drivers recognized the inherent risks involved in automobile racing, and they believed that practice and skill were the key components to success within the sport.

Members of the press and racing insiders also expressed contemporary views about risk-taking and masculinity in their discussions of racing accidents. One reporter offered his conviction that motorsports “breeds men” who remain “calm and strong in a vortex of horror and fear.”[23] In the minds of their contemporaries, racecar drivers exhibited several tenets of masculinity, including courage, technical expertise, and the ability to think quickly under pressure.[24] Racing enthusiasts praised racecar drivers for their ability to pay close attention to sensory cues signaling mechanical problems with their racing machines and commended drivers who steered their ailing cars to safety before a serious accident occurred on the track.[25] When a racecar driver’s life ended on the speedway, reporters and racing insiders expressed their admiration for these daredevils who died doing what they loved. After one specific racing incident that resulted in the death of two racecar drivers, AAA official Ted Allen expressed his hope that the drivers’ families were comforted by the fact that “these men matched their courage against the risk of the enterprise and had they known it was their time they would have wished rather such a close to an eventful life than to rust unburnished.”[26] Through their eulogies to fallen drivers, Americans expressed their views that dangerous activities, such as automobile racing, were honorable occupations for men during the 1920s and 1930s.

When racecar drivers did lose one of their own, they often contended that continuing their own racing careers was the best way to memorialize their fallen peers. After Ray Keech lost his life at Altoona in 1929, fellow Philadelphian and close friend, Fred Winnai, was so shaken by Keech’s death that he briefly retired from racing. However, Winnai returned to the sport and again entered races before the close of the 1929 season.[27] A year after Keech’s death, the press indicated that Winnai was jockeying for a ride in the Yagle’s Miller Special, the same racecar that Keech had drove to his death at Altoona.[28] Even after witnessing the accidents of their close friends, racecar drivers continued to pursue their own racing careers, attempting to beat the speed records of their fallen peers.

Lucky Charms

Each racecar driver developed different strategies to compartmentalize the risk they faced on the speedway. Sports reporter, Henry McLemore, informed readers of the Shamokin-News Dispatch that automobile racers were more superstitious than any other group of athletes. He claimed that almost every driver had “a certain ritual they must perform before stepping into their cars.”[29] McLemore’s statement seems to contradict racecar drivers’ insistence on their ability to control their racecars due to a mixture of skill, intuition, and experience; however, several of the nation’s leading automobile racers did participate in rituals as an added insurance policy at the speedway. Three-time AAA National Champion, Ted Horn developed a long list of superstitions while racing on the AAA circuit during the late 1930s. Horn would not allow peanuts anywhere near his racecar. He refused to be photographed before a race. He would not shave on race days. And, he never wore green at the speedway. Horn’s superstitions seemed completely irrational, but Horn connected each of these “jinx’s” with the pre-race actions of fellow racecar drivers before their own fatal racing accidents.[30] Several racing veterans joined Horn in avoiding such jinxes at the speedway. Some men went even further by outfitting their race teams in a specific color they deemed to be good luck. Others tied family mementoes to their steering wheel or glued pictures inside their racing cockpits.[31] Drivers firmly believed that fate and luck played an active role in their racing careers.

Drivers who competed at dirt track races in their local communities all aspired to be the next Frank Lockhart or Ray Keech and race to victory in the Indianapolis 500. However, AAA racecars remained prohibitively expensive for the majority of American men who desired to become the nation’s next speed king.[32] Rookies often lacked close connections with the nation’s leading racecar builders and automobile manufactured-sponsored teams. As a result, they willingly climbed into cars that had previously been involved in serious accidents and undergone major repairs if that would give them a chance to compete on the AAA circuit. Members of the press often referred to these racing machines as “death cars” because of their unfortunate provenance.[33] However, young drivers looking for a chance to prove themselves on the speedway climbed into the racecars of their fallen peers believing that their skills and a little luck would allow them to avoid a similar fate.

By the time Frank Farmer climbed into the driver’s seat of the Yagle-Miller Special at the start of the 1930 racing season, some racing fans were beginning to spread rumors that the racecar was jinxed. Less than three months after Ray Keech had lost his life in the Yagle’s racecar at Altoona, Jimmy Gleason suffered serious injuries when he flipped the repaired racecar in a race on Long Island.[34] Farmer, a former theology student, denied he believed in such bad omens.[35] Reporters joked, however, that they had seen a rabbit’s foot hanging from Farmer’s radiator at the June 1930 race at the Altoona board track.[36] Whether it was his lucky rabbit’s foot or his own skill behind the wheel, Farmer set a new lap record at Langhorne Speedway, a one-mile dirt oval located near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in early July 1930.[37] Over the next two racing seasons, Farmer and a series of other drivers continued to ignore the skeptics and raced the Yagle-Miller Special at oval tracks located across the mid-Atlantic (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Maude Yagle

As more and more car owners began to purchase new racecars, the Yagle’s Miller was no longer competitive at Indianapolis, but the car remained a coveted ride on the eastern fairground circuit.[38] Racing in cars that had previously been involved in serious accidents was a reality of the sport in the 1920s and 1930s. Frank Farmer and other drivers ignored the skeptics to have a chance to win races and advance their own racing careers.

During a race in August 1932 at Woodbridge Speedway in New Jersey, Frank Farmer’s luck finally ran out. While driving the Yagle-Miller Special, Farmer collided with another racecar driven by Bill Neapolitan during a heat race. Both drivers died as a result of the collision.[39] Farmer would be the last thrill-seeker to vie for fame and glory behind the wheel of the Yagle-Miller Special. After seven years on the AAA racing circuit, the Yagle-Miller faded from the sports pages.

Conclusion

Americans read stories about heroism on the speedway, featuring drivers, such as Frank Lockhart, Ray Keech, Jimmy Gleason, and Frank Farmer, who pushed their racing machines to new speed records and exciting speedway victories. While automobile racing gained popularity as an American pastime during the interwar period, participants viewed themselves as more than just outdoor entertainers. Racing enthusiasts consistently argued that automobile racers’ most important role was as innovators and testers of automobile technology. Technology-centered hobbies, such as automobile racing, provided Americans with a platform to express cultural anxieties about the risks technology created in their daily lives. After watching thrilling victories and fatal accidents on the speedway, Americans, such as Mrs. Keech, resigned themselves to the fact that, while they could try to combat technological risks with skill and mechanical expertise, ultimately, their lives were left up to fate.

[1] Alison Kreitzer is a Ph.D. candidate in the History of American Civilization Program at the University of Delaware. She is currently working on a dissertation examining twentieth-century dirt track automobile racing in the eastern United States. Special thanks to Dr. Arwen Mohun, Marionne Cronin, and members of my dissertation writing group for their feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

[2] Captain E.V. Rickenbacker, “Bright Future Seen For Auto Racing,” Altoona Tribune, January 5, 1929, 1.

[3] Randall L. Hall, “Before NASCAR: The Corporate and Civic Promotion of Automobile Racing in the American South, 1903-1927,” The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 68, No. 3 (August 2002): 629-668.

[4] “Keech Killed, Woodbury Is Hurt In Crash,” Altoona Tribune, June 17, 1929, 1.

[5] During the early twentieth century, Americans discussed and debated how technological innovations, such as the automobile, had significantly impacted the pace of daily life within the United States. See, Stephen Kern, The Culture of Time and Space, 1880-1918 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983), 109-130; Ronald Kline, Consumers in the Country: Technology and Social Change in Rural America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000); Clay McShane, Down the Asphalt Path: The Automobile and the American City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004); Reynold M. Wik, Henry Ford and Grass-Roots America (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972); Michael L. Berger, The Devil Wagon in God’s Country: The Automobile and Social Change in Rural America, 1893-1929 (Shoe String Pr Inc,, 1979); and Kenneth L. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 157-171.

[6] Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the 19th Century (Berkeley: The University of California Press, 1986), 33-66.

[7] For further reading on the rise of an urban consumer amusement industry within the United States, see: John F. Kasson, Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century, (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978); Judith A. Adams, The American Amusement Park Industry: A History of Technology and Thrills (Twayne Publishers, 1991); Itai Vardi, “Auto Thrill Shows and Destruction Derbies, 1922-1965: Establishing the Cultural Logic of the Deliberate Car Crash in America,” Journal of Social History, Vol. 45, No. 1 (2011): 20-46; Andrea Stulman Dennett and Nina Warnke, “Disaster Spectacles at the Turn of the Century,” Film History, Vol. 4, No. 2 (1990): 101-111.

[8] Ben Shackleford argues that the multi-sensory spectator experience at an automobile race is an example of David Nye’s concept of the “technological sublime.” Shackleford further contends that the sensory and emotional experience Americans had at NASCAR races helped to reinforce political and cultural beliefs about masculinity, machinery, and risk among Southerners. See, Ben A. Shackleford, “Masculinity, the Auto Racing Fraternity, and the Technological Sublime: The Pit Stop As a Celebration of Social Roles” in Boys and Their Toys? Masculinity, Class, and Technology in America, ed. Roger Horowitz (New York: Routledge, 2001): 229-248. For a full discussion of the technological sublime, see: David Nye, The American Technological Sublime (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1994).

[9] L.J. Bergere, “General AAA Bulletin,” Vol. IV, No. 21 (July 11, 1929):1, Eastern Museum of Motor Racing (EMMR) Microfilm Collection.

[10] George Stephens Clark, “Gasoline and Sand: The Birth of Automobile Speed Racing,” Mankind: The Magazine of Popular History Vol.3, No.4 (1971): 18.

[11] Clark, “Gasoline and Speed,” 21.

[12] Bergere, “General AAA Bulletin,” 3.

[13] Major H.O.D Segrave, The Lure of Speed (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1928): 278.

[14] Segrave recalled that gusts of wind during his attempts to set a new World’s Land Speed Record on the sands of Daytona, Beach Florida seemed to distort time, making any steering adjustment during the run feel like it was taking an eternity to complete. See, Segrave, Lure of Speed, 252.

[15] “Frank Lockhart Killed Trying for New Record,” Circleville Herald, April 25, 1928, 1.

[16] Exemplifying our continued cultural fascination by horrific automobile crashes, 21st century Americans can still view the original footage of Frank Lockhart’s fatal crash at http://www.britishpathe.com/search-/query/Frank+Lockhart.

[17] Bergere, “General AAA Bulletin,” 2.

[18] “Frank Lockhart Killed Trying for New Record.”

[19] Speed limits varied from state to state in the early 1930s, and fifteen states did not have state-wide speed limits. If drivers were involved in an accident and traveling over a specific speed in some states, they were automatically fined for reckless driving no matter who was at fault for the collision. See, Lorena Hickok, “Speed Limits Are Raised Throughout the Country; Vacationists Can ‘Step Up,’” Fitchburg Sentinel (Massachusetts), June 17, 1931, 10.

[20] Kevin Nelson, Wheels of Change From Zero to 600 M.P.H. The Amazing Story of California and the Automobile (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2009), 176.

[21] “To Muse & Amuse by Sports Editor,” Altoona Mirror, June 17, 1929, 17.

[22] Driver Johnny Hannon dominated at eastern speedways during the early 1930s and won the AAA Eastern Championship in 1934. In 1935, Hannon died during his first qualifying lap at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The drivers who witnessed Hannon’s fatal accident blamed his death on his inexperience at the speedway. See, “3 Race Drivers Die on Speedway at Indianapolis,” Gazette and Daily (Pennsylvania), May 22, 1935, 1.

[23] “Met Heroic Death at Sea,” Wilmington News-Journal (Ohio), November 17, 1928, 1.

[24] Americans increasingly negotiated gender roles through leisure activities and sports at the turn of the twentieth century. White men used physically strenuous activities, such as contact sports and hiking, as a way to promote their gender and racial superiority. See, Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996); Clifford Putney, Muscular Christianity: Manhood and Sports in Protestant America, 1880-1920 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001); and Donald J. Mrozek, Sport and American Mentality, 1880-1910 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1983).

[25] At the 1926 Indianapolis 500, Norman Batten received significant press attention for piloting his flaming racecar to safety at the bottom of the speedway. Batten suffered significant burns by staying with his racecar, but his actions prevented the flaming car from going off the track towards the main spectator grandstand. See, “Young Lockhart Favorite to Win 500-Mile Classic,” Harrisburg Telegraph, May 30, 1927, 1; “Norman Batten, Boro Boy, Burned As Car Goes Afire,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 30, 1927, 1; “Dramatic Race Won by a Tyro,” Independent Record, May 31, 1927, 7; and “Will Ask Congress to Give Recognition to Race Driver’s Heroism,” The Bee, June 2, 1927, 1.

[26] Ted Allen, “Official Bulletin,” Vol. V, No. 34 (July 1, 1930): 1, EMMR Microfilm Collection.

[27] “Winnai Expected to Drive Keech’s Former Car in Flag Day Race, Meyer and Gleason Sign Up,” Altoona Tribune, June 4, 1930, 12, and “Altoona Ready for Motor Classic Flag Day, June 14,” Indian Gazette, June 6, 1930, 12.

[28] Winnai did not end up racing the Yagle-Miller Special at Altoona in June 1930. Frank Farmer drove the racecar to a third place finish at the event. See, “Frank Farmer Tunes Car to Drive Race,” Altoona Mirror, June 13, 1930, 17 and “Speed Aces Will Start Trials Today,” Altoona Tribune, June 12, 1930, 1.

[29] Henry McLemore, “Today’s Sports Parade,” Shamokin-News Dispatch, September 18, 1933, 10.

[30] Russ Catlin, The Life of Ted Horn: American Racing Champion (Los Angeles: Floyd Clymer, 1949): 90-92.

[31] “Speedways Will Miss Billy Winn of Detroit,” Escanaba Daily Press, August 23, 1938, 12 and Henry McLemore, “Today’s Sports Parade,” Shamokin News Dispatch, September 18, 1933, 10.

[32] William F. Sturm served as Lockhart’s manager throughout his racing career and was actively involved in the Indianapolis auto racing community. In an article published in the Indianapolis News in 1930, Sturm stated that M.A. Yagle had purchased the Lockhart car for $6,100. His article discussed that the majority of cars racing in the 1930 Indianapolis 500 cost under $8,000, while a few outliers cost as little as $3,000 or as much as $15,000 (See “Speedway Appetizers,” May 19, 1930, 23). Lockhart’s most recent biographers, Sarah Morgan-Wu and James O’Keefe state that Lockhart’s estate was valued at $27,033. They argue that Yagles paid $14,707.67 for the Miller 91 (appraised at $5,000) and various tools (appraised at $5,725). See, Morgan-Wu and O’Keefe, Frank Lockhart: American Speed King (Boston: Racemaker Press, 2012).

[33] For a May 1932 race at Reading Speedway, three different “death cars” were entered in the race. Zeke Meyer was set to pilot Ray Keech’s former car, owned by Mrs. Maude Yagle, Billy Winn sat behind the wheel of Bernie Katz’s former car, and the driver’s seat was still open for the car that Bob Robinson died in at Woodbridge Speedway in 1930. See: “Zeke Meyer Enters Sunday Race Meet,” Reading Times, May 12, 1932, 16.

[34] “Mrs. Yagle’s Racing Car Again Wrecked,” Shamokin News-Dispatch, September 23, 1929, 1.

[35] “Bob Carey, Holder of Track Record, To Race at Bloomsburg,” Pittston Gazette, June 28, 1932, 7.

[36] “Speedway Sidelights,” Altoona Tribune, June 16, 1930, 1.

[37] “Car of Former Local Woman Holds Dirt Track Record,” Shamokin News-Dispatch, July 8, 1930, 1.

[38] “Gasoline Gigolos Cause of Flutter in Girlish Hearts,” Reading Times, July 13, 1932, 14.

[39] “Frank Farmer and Neapolitan Killed in Auto Race Crash,” Reading Times, August 29, 1932, 10; “2 Race Drivers Die In Crash,” Altoona Tribune, August 29, 1932, 1; “2 Auto Racers Die In Woodbridge Crash,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 29, 1932, 6; and “Two Auto Racers Killed in Crash,” Daily Capital Journal, August 29, 1932, 3.