“Feminine Waste Only!!!” A History of the UK Sanitary Bin in the Twentieth Century

Technology’s Stories vol. 6, no. 3: DOI: 10.15763/jou.ts.2018.08.20.03

PDF: Rostvik_Feminine Waste Only

Every fortnight one man enters all the women’s toilets at our university, removes and replaces the sanitary bins, and drives away in a van. Observing this system, I became curious about the grey rectangle with foot-operated pedals, “modesty flaps”, bearing the warning “for feminine waste only”, located in almost every women’s toilet in the UK. The sanitary bin turns out to be a symbol-heavy plastic object in the modern history of waste management and meaning, entangled in changing ideas about the environment, women’s role in the workplace, profit, technology, and bathroom politics

Figure 1. Typical (PHS) sanitary bin at the University of St Andrews, 2018. Photo: Røstvik.

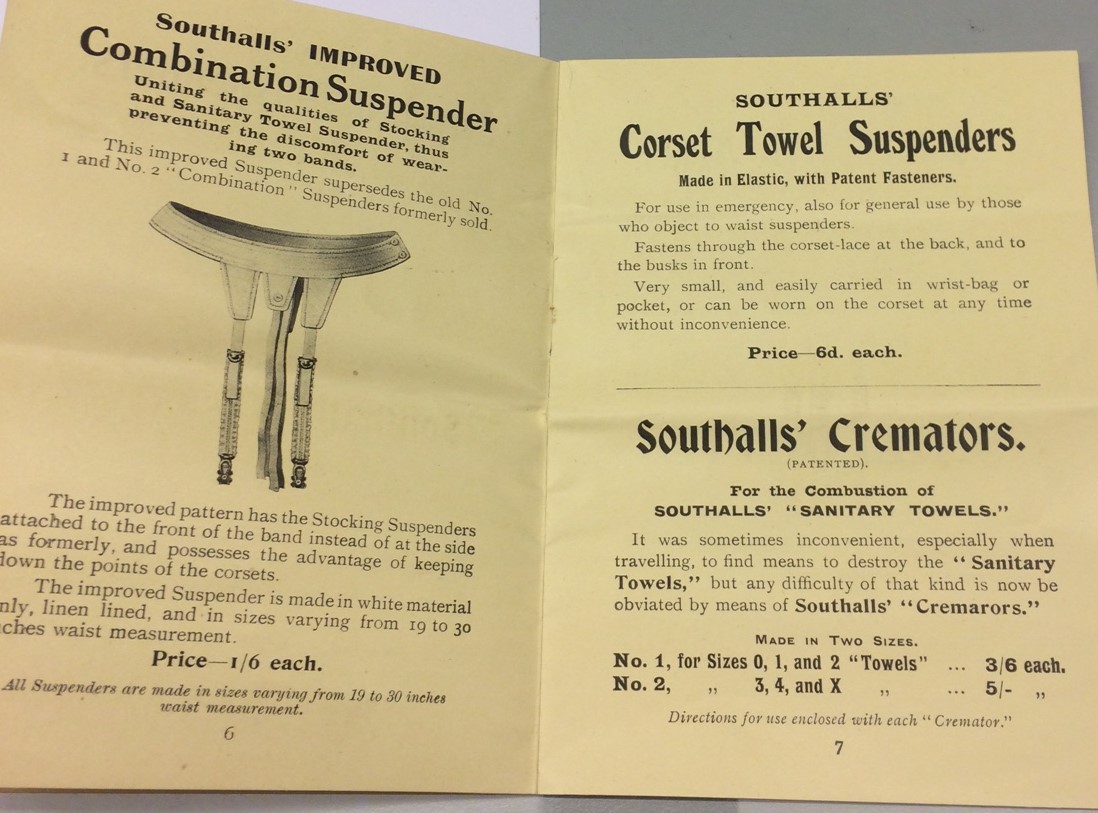

Burning evidence in the early twentieth century

In the early twentieth century, British public bathrooms only sporadically included solutions for managing the relatively new waste caused by disposable menstrual products.[1] In some buildings frequented by women you might find an incinerator, designed to burn the used products. A leaflet from 1916 gave details of a “Southalls’ Cremators (patented)” for the combustion of “Southalls’ Sanitary Towels”, providing early evidence of the link between the increased popularity of disposable menstrual products and the need for waste management in the UK.[2]

Figure 2. Southalls’ Cremators”, Southalls’ Sanitary Requisites leaflet, 1916. Wellcome Collection.

These solutions were not consistent, and the incinerators were often blocked, smelly or not functioning. Thus, in the early twentieth century, most bathrooms users were left with no other option than flushing, hiding, or carrying used items out of the space.

During the Second World War, the Medical Women’s Federation (MWF) set up a “Menstruation Leaflet Committee”, which took a keen interest in the problem:

Endless trouble was encountered in persuading service women to use the bins and wrapping paper provided, and the storage of soiled towels behind pipes, in drawers, and down lavatories was one of the real trials of N.C.O.S. and officers.[3]

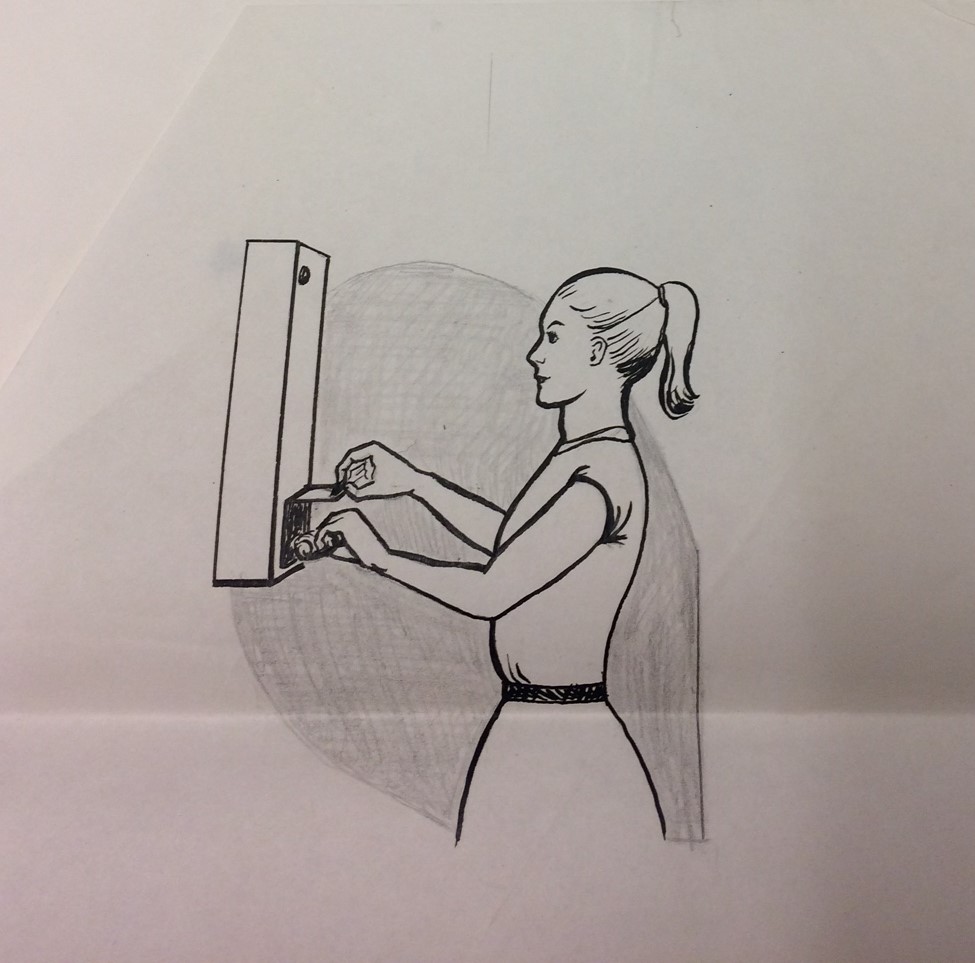

The MWF pointed out that “disposal is a relatively new problem. Up to fairly recently, nearly all women, and many poorer women still, use washable articles.”[4] Following a 1949 school survey, MWF was shocked to find that few schools provided waste management: “it seems inexcusable that 75/112 schools have neither bins or other disposable method.”[5] Ten years later, the MWF and the Scottish Council for Health Education went on to suggest a solution which would become the one we know today: provision of a small bin in each washroom, with paper bags, and instruction notices stating “Please Do Not Flush Feminine Products Down the Toilet!” Waste, in turn, should be emptied into an incinerator or furnace off-site, with the warning that “this work should not be left to male staff.”[6]

ure 3. “Incinerator”, MWF draft illustration for “Menstruation leaflet 1963-1968”. Wellcome Collection.

By the 1950s, then, the stage was set for entrepreneurs to solve the problem of menstrual product disposal, and cash in on the solution.

The Comdiscan in the 1950s

Ever since Thomas Crapper patented the modern toilet in the 1880s, entrepreneurs sought to capitalise on the new public interest in hygiene. Early patents included inventor George S. James “sanitary waste disposal bin”, patented in New York in April 1952 as “a convenient method of disposing of sanitary napkins.”[7] In the UK, Cannon Hygiene lays claim to being the pioneer on their websites: “Back in 1955, Cannon Hygiene revolutionised feminine hygiene by introducing the first ever feminine hygiene disposal units”.[8]

Figure 4. Original-style blue Cannon Hygiene bins from the 1950s, at Falkland Palace, 2018. Photo: Røstvik.

According to the website, wife and husband team Alys and Stanley Ostle Kennon[9] started the first sanitary exchange unit system; the Comdiscan, which stood for “a COMplete DISposal of all waste by CANnon”.[10] The bins were, then as now, rectangular in order to fit into the slim space between toilet and wall, with later versions sporting “modesty flaps” (industry speak for the plastic lids that block any view into the bin) and foot-operated pedals (the first models were hand operated). The design was simple and the plastic cheap, but the marketing of it as a “special sanitary bin” caught the attention of the growing number of employers with increasing female workforces.

Whilst Cannon Hygiene capitalised on the production of this new plastic item, competitors like PHS and Rentokil bought or borrowed the bins for the brand-new system of “sanitary unit exchange”. The system meant that drivers would service employer’s buildings, removing dirty bins, and replacing them with clean units. Back at the depots, a largely female workforce in wellingtons and plastic dress covers would tip the contents into a fire, and clean the units. One company, PHS, did this particularly well.

The 1960s business boom

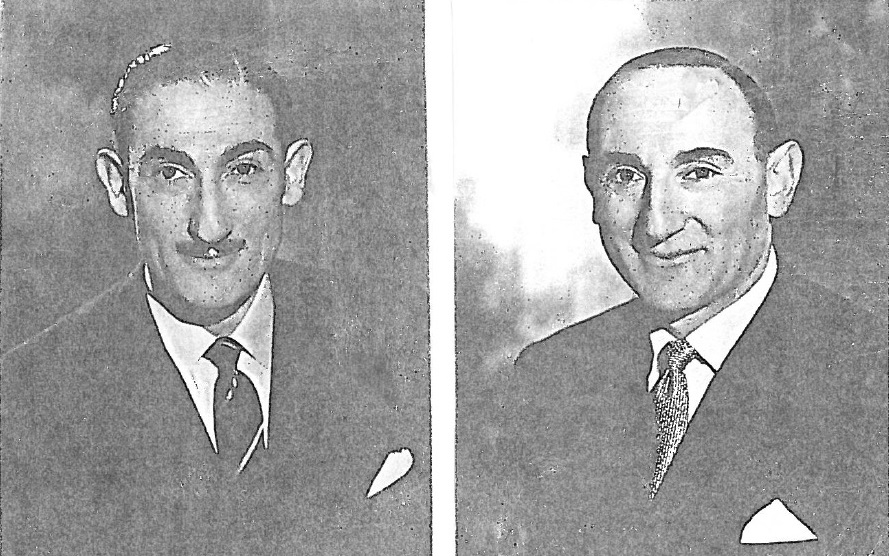

In 1963, the same year the MWF and Scottish Council suggested bins as a waste solution, entrepreneurs and brothers George and Alfred Tack (1906-1993/1995) founded Track Retail Consultants (PHS from 1966).[11] According to one former employee, the origin story for PHS revolves around the Tacks’ unnamed female secretary who came across the suggestion in a pile of proposed business ideas. Sensing a business opportunity, she talked to the brothers about the sanitary bin exchange system as an investment idea. Alfred and George took a chance, and by the time the company changed name to PHS, it was one of the biggest success stories in the waste industry. Fittingly, even the brothers name seems to reinforce their commitment to the ballooning sanitary industry. “Tack” may have originated in the French word “tache”, originally meaning spot or stain.

Figure 5. Alfred and George Tack, origin and date unknown. Right to republish image from Eric Pillinger.

“Environmenstrualism” and normalisation in the 1970s and 80s

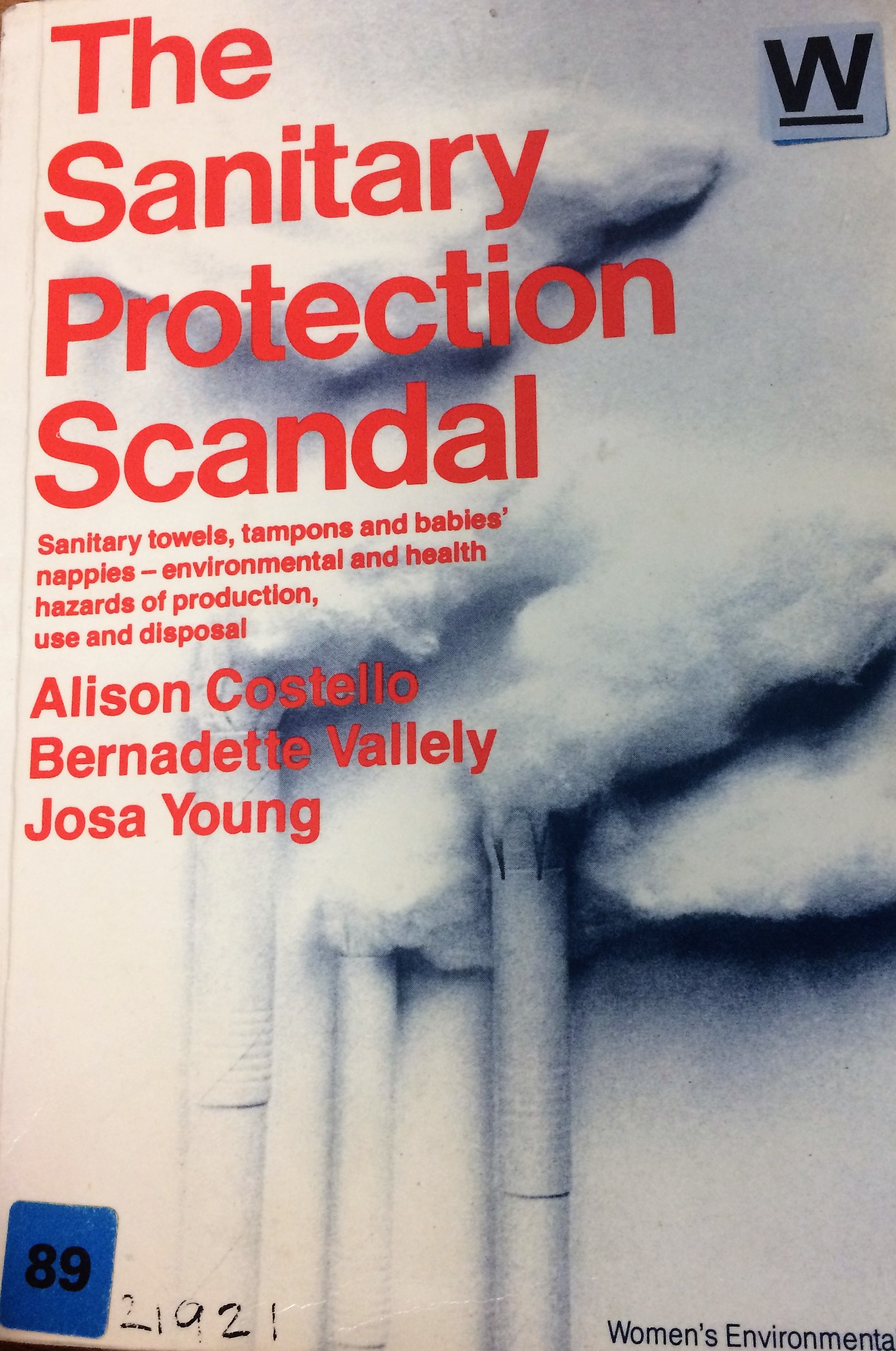

Once the sanitary bin exchange system was established by Cannon Hygiene, PHS and their competitors, it grew in tandem with the explosion of menstrual product use and the growth of the female workforce in the 1970s and beyond. Environmental activists, specifically the Women’s Environmental Network (WEN) in the UK, began advocating for better waste solutions. Emerging during the Women’s Liberation Movement, WEN’s history started intersecting with sanitary bin service providers in the late 1970s, when they argued that tampons, pads, applicators and diapers generated vast and unmanageable amounts of waste in the UK, which in turn had consequences for landfill, air (through incineration), plumbing, and oceans.[12] WEN wrote that women did not want to flush the items, but were often left with no option:

The immediate problem of disposal for women occurs in public places where there is inadequate or no provision for disposal (…) As women, we are faced with the problem of whether to dispose of our used sanitary towels/tampons down the toilet or take them home with us. The amount of time and money wasted by fixing drains blocked by sanitary products must be taken into account when considering disposal problems. In publically-owned properties it is the public who pay for these drains to be unblocked.[13]

Figure 6. Cover of WEN’s 1989 publication The Sanitary protection Scandal.

WEN’s “environmenstrual campaigning” was covered in mainstream British media, and helped change attitudes about flushing products, and also set the stage for the next chemically-focused phase in the sanitary bin industry.

Bactericide and law in the 1990s

WEN’s call for action coincided with new research done by the sanitary bin sector, notably Rentokil’s often-cited 1979 bacteriological survey of over 400 used sanitary products.[14] This showed that over 70 per cent of used items were contaminated with fecal matter and bacteria.[15] The work was timely, published just as the Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS) crisis relating to Rely tampons and Procter & Gamble in the US exploded in 1980. This resulted in global public debate about menstrual product hygiene and safety, especially concerning the TSS-related bacteria staphelicocus aureus –mentioned several times in Rentokil’s paper.[16] Employers scrambled to find solutions to these concerns as HIV/Aids debates further politicized questions of blood. Rentokil’s research suggested the need for a bactericide and chemical solutions in sanitary bins, and this quickly became the norm in an era of blood fear. By the mid-1980s, then, the industry could provide a solution for both environmental and toxicity fears, which soon became the subject of legal action.

Figure 7. Typical “warning” in women’s bathrooms. Photo: Røstvik.

New laws and regulations in the 1990s meant that any workplace in which women who might be menstruating were employed had to come to grips with the disposal of menstrual product waste.[17] Reflecting changes in the law, the industry added information about how their services could quickly and “discreetly” solve the legal headache for employers. And so, by the mid-1990s, sanitary bins became normal, even expected, items in any public bathroom.

The future of the industry

After normalization, the 2000s mark a turn towards increased use of chemicals and aesthetics at the high-end of the industry, while most toilets are still outfitted with older pedal-operated models. An overall turn towards more aesthetically pleasing restrooms were spurred on by the 2010s “bathroom selfie” trend, the UK “Loo of the Year” campaign to raise overall standards, and debates about bathroom politics and gender.[18]

Chemicals, however, remain the strongest selling point. An industry-standard list of protections offered by the average bin today includes E.coli, salmonella and MRSA, HIV, staphelicocus aureus, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C.[19] But beyond Rentokil’s study, written in the midst of the 1980s TSS and HIV crises, there is little evidence to suggest that all of these dangers actually lurk in a sanitary bin. In many countries, of course, women’s toilets are still outfitted with a normal bin or small paper bags. Despite this, the UK industry has engaged in a technological and chemical warfare since the millennium, with an ultimate goal of creating a completely sterile environment in the bathroom whilst ultimately continuing to send the “lethal waste” to landfills.

Today, PHS and its competitors all point out the environmental and climate change related dangers of relying too much on landfills, suggesting burning waste and reverting it to energy as a possible future solution.[20] But so far, these pioneering systems have been located sparely around the country, meaning that the entire business continues to rely heavily on trucks that transport bins nationally. Meanwhile, contemporary menstrual activists are again concerned with the environment, as hinted by the rise of plastic-free reusable products like washable cloths and cups, thus challenging the necessity for sanitary bins in the long run.[21] The parallel increase in the use of hormonal contraceptives that lighten or exclude menstruation altogether, show that the need for sanitary units may not be so acute after all. At the same time, trans-men and non-binary people who need sanitary bins are left to flush or hide used products, as women did in the 1950s.

Conclusion

What then, are we to make of the object in the corner of the room? Campaigner Chella Quint worries about the symbolism of these units, as they seem to function as constant reminders to women about their bodies’ “biohazardous” status[22], wheras WEN continue campaigning for better “environmenstrual” policies. But is the industry listening?

It is notable how persistent myths about menstruation are in an industry profiting from women. Ideas about menstrual blood as toxic have shaped the British industry into a successful solution for an exaggerated problem. There is little scientific evidence to suggest that menstrual product waste is toxic, but the industry continues building its case on this assertion, often citing Rentokil’s 1980 survey. These attitudes play neatly into the longer history of menstrual mythology, starting with Pliny the Elder’s fear that periods turned crops barren and gardens dry, and climaxing with the 1920s debate about “menotoxins”; deadly menstrual blood.[23] In general, the lack of scientific studies regarding the properties of menstrual blood has served the sanitary bin industry well.

At the same time, the gender dynamics in the industry have also changed. As companies have included more unisex services (soap, toilet roll, etc.) men entered the industry and today dominate in the combined roles of driver-cleaner, jobs that are challenging and low paid. This gendered work intersects with current debates about identity and bathroom politics in a modern era when segregation between women and men became normal.[24] The British sanitary bin industry has not championed the inclusion of their products in men’s toilets for trans and non-binary people, despite the obvious business opportunity.[25] Instead, they seem to be unwittingly and unknowingly championing inclusiveness in bathrooms by hiring mostly men to enter women’s restrooms.

Encountering a sanitary bin today, in all its grey “modesty flapped” glory, links us to a history of profit, environmental activism, menstrual politics, and gender dynamics far more interesting than the promises of discretion and protection it claims to solve.

Dr Camilla Mørk Røstvik is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of St Andrews. She is working on a project entitled ‘‘The Painters Are In’ – The Art History of Menstruation since 1950’.

Suggested Readings

Costello, Vallely, Young, The Sanitary Protection Scandal: Sanitary Towels, Tampons and Babies’ Nappies – Environmental and Health Hazards of Production, Use and Disposal. London: Women’s Environmental Network, 1989.

Sheila L. Cavanagh, Queering Bathrooms: Gender, Sexuality, and the Hygienic Imagination. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Breanne Fahs, Out for Blood: Essays on Menstruation and Resistance. New York: SUNY, 2016.

Sharra L. Vostral, Under Wraps: A History of Menstrual Hygiene Technology. New York: Lexington Books, 2008.

[1] On the beginning and growth of the disposable menstrual product industry, see Sharra L Vostral, Under Wraps: A History of Menstrual Hygiene Technology. New York: Lexington Books, 2008.

[2] Jevons & Mellor, ‘Southalls’ Sanitary Requisites’. Southall’s: Birmingham, 1916. Wellcome library, general collection, P/942.

[3] ‘Notes on Lancet article (published 28 May 1949)’, Menstruation Leaflet Committee 1930s-1960s, Wellcome Library, General Collection: SA/MWF/B/4/5: Box 8 (6), p 2.

[4] Ibid, p 5.

[5] Ibid, p 6.

[6] Medical Women’s Federation and the Scottish Council for Health Education, Feminine Hygiene. Edinburgh: C.J. Cousland & Sons Ltd., 1963. Wellcome library, general collection: SA/MWF/B/4/5: Box 8, p 7-8.

[7] Patent number US2593455, patented 22 April 1952. United States Patents office.

[8] ‘Feminine Hygiene Services’, Cannon Hygiene UK website: https://www.cannonhygiene.com/services/washroom-care/feminine-hygiene (all websites accessed 3 August 2018). Cannon have not responded to requests for further information.

[9] Alys is not named on the website, but her name appeared in a 2015 newspaper article about Cannon Hygiene.

[10] ‘History’, Cannon Hygiene India website: https://cannonhygieneindia.com/history. The same history appears on all international Cannon Hygiene websites, but there are different accompanying images.

[11] Eric Pillinger, TACK International booklet. London: T. International, 2017.

[12] ‘Environmenstrual Campaign’, Women’s Environmental Network website: https://www.wen.org.uk/environmenstrual/

[13] Alison Costello, Bernadette Vallely, Josa Young, The Sanitary Protection Scandal: Sanitary Towels, Tampons and Babies’ Nappies – Environmental and Health Hazards of Production, Use and Disposal. London: Women’s Environmental Network, 1989.

[14] M.F. Mendes, C.M. Lucas, “A Bacteriological Survey of Sanitary Dressings, and Development of an Effective Means for their Disposal”, 1980. The Journal of Hygiene 84 (1): pp 41-46.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Vostral, “Rely and Toxic Shock Syndrome: A Technological Health Crisis”, 2011. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 84 (4): pp 447-459.

[17] Influentially, the Environmental Protection Act of 1990 imposed a Duty of Care on organisations that produced, kept or disposed of sanitary waste. The 1991 Water Industries Act stated that no sanitary waste should be flushed away if it could cause harm to a sewer or drain. The Workplace (Health, Safety & Welfare) Regulation from 1992 recommended that all businesses should ensure that female toilets are provided with a suitable method of disposing sanitary waste. The 2005 Hazardous Waste Regulations stated that the responsibility for determining if waste is dangerous rests with the producer.

[18] One of the origins of the popularity for the ‘bathroom selfie’ can be tracked down to Kim Kardashian’s book Selfish: Milan: Universe Publishing, 2015.

[19] Websites Cannon Hygiene, PHS, Rentokil, and smaller competitors.

[20] ‘LifeCycle ™’, PHS website (2018): www.phs.co.uk/lifecycle

[21] About contemporary menstrual activism see Breanne Fahs, Out for Blood: Essays on Menstruation and Resistance. New York, SUNY, 2016; Chris Bobel, New Blood: Third-Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation. Rutgers University Press, 2010.

[22] Quint interviewed in Kira Cochrane, “It’s in the Blood”, The Guardian, 2 October 2009.

[23] Janice Delaney, Mary Jane Lupton, Emily Toth, The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation. Urbana and Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 1976.

[24] Gender segregated toilets became more normal in the mid-eighteenth century, see Sheila L. Cavanagh, “You Are Where You Urinate”, Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide 18.

[25] Cavanagh, Queering Bathrooms: Gender, Sexuality, and the Hygienic Imagination. Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2010.