Notes from the Field: Roswell, New Mexico

Technology’s Stories vol. 5, no. 1 – doi: 10.15763/JOU.TS.2017.4.1.04

PDF: Bimm_Notes From the Field

Aliens have invaded Roswell.

Whether or not you believe a UFO really crashed here in the summer of 1947, what’s readily apparent is that the image of the almond-eyed extraterrestrial is everywhere. Restaurants, motels, liquor stores, gift shops, car dealerships, and loan offices all trade in the icon of the so-called “little green man”. These, of course, reference the infamous cold war-era conspiracy theory that a downed alien spacecraft was recovered near-by, and reverse-engineered by the United States military. “The Roswell UFO Incident,” as it has become known, remains one of the iconic technological mysteries of the twentieth century, and is now part of mainstream American folklore. This story, revived and popularized in the late 1970s by nuclear-physicist-turned-Ufologist Stanton T. Friedman and others, has helped animate an entire worldview based around belief in a wide-reaching government conspiracy to conceal the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence and technology. However, in Roswell, the ever-present alien and UFO myth obscures other layers of technological history.

In the autumn of 2015 I found myself on a six-week-long research-and-speaking road trip around the Southwestern United States. It began with a talk at the Society for the History of Technology (SHOT) in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and took me through Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, Utah, and California. My first stop after SHOT was the archive at the New Mexico Museum of Space History, in Alamogordo, home of the White Sands Missile Range, Holloman Air Force Base, and the International Space Hall of Fame. This put me only two hours—striking distance—west of Roswell, a place that had fascinated me since childhood.

But why should serious historians of technology care about contested, counter-factual, or conspiratorial pseudo-histories, like the Roswell UFO incident? First, as any space historian will tell you, it’s bound to come up in conversation.[1] Space history, unlike other areas of history of technology, has to contend with two especially pervasive myths: the moon landing hoax, and UFOs. So better have a smart, well-informed answer ready to go. Beyond the practical, these stories—whatever truth there might be to them—tell us about popular notions and attitudes about technology, in this case belief in the existence of powerful technologies kept secret. But what makes Roswell so interesting is that here the normal state of history of technology is inverted; the myth is mainstream, and verifiable technological stories are relegated to the fringe. So as I prepared to immerse myself in UFO lore and spectacle, I was also interested in the lesser-known episodes at the margins of this old base-and-cattle town.

Driving in, my first stop was the International UFO Museum and Research Center. Housed in an old converted movie theatre, it was founded in 1992, just on the cusp of what would be a decade of increasing interest in the Roswell Incident. Thanks to mentions in television programs and films such as The X-Files, Independence Day, Men In Black, Futurama, and the short-lived teen drama Roswell, the town’s name became synonymous with UFOs, extraterrestrials, and government conspiracies.

The museum is essentially one large room, with displays lining the walls. These begin with an account of the basic Roswell myth—that metallic debris was recovered in a rancher’s field after a fierce summer thunderstorm in 1947, and that initial media reports about a captured “flying disc” were quickly watered down to a crashed weather balloon, ending interest in the story. The displays, featuring timelines, news clippings and eyewitness testimony, are not fancy—many are simply text-heavy paper printouts and black and white photographs stapled to the wall. However, this section of the museum does reveal how the Roswell myth connects up with a verifiable story about classified technology and extreme government secrecy early in the cold war.

Back in 1947, Roswell Army Airfield was home to the 509th Bomb Wing, famous for dropping the first atomic bombs on Japan two years earlier, and by then one of ten nuclear bombardment units under Strategic Air Command. Roswell believers argue that America’s expanding nuclear capabilities drew curious or concerned extraterrestrials to the area. Critics point to the known culture of secrecy and exotic technology surrounding nuclear weapons to explain any suspicious behavior, and to the military’s classified Project Mogul—an attempt to use high-altitude balloons launched from Alamogordo to surreptitiously detect signs of Soviet nuclear detonations—as the source of debris that could not be publicly acknowledged.

A towering replica of the alien robot Gort from the 1951 sci-fi classic The Day The Earth Stood Still signals the widening of the collection’s scope to encompass the general theme of aliens and UFOs. The eclectic collection contains everything from folk art renderings of aliens, blurry photographs of lights in the sky, and dioramas depicting Nazi officers working on saucer-shaped aircraft.

Fig 1. UFO Model

At the center of the massive space is the pièce de résistance, a large model of a (safely) landed UFO—its crew of four human-sized aliens disembarked, standing ready to make contact. Every 20 minutes or so the static display springs to life: clouds of dry ice billow out accompanied by pitch-shifted “alien chatter” and laser sounds, as the UFO spins in place. Exiting through the large gift shop that sells all kinds of extraterrestrial swag—including bottles of “UFO H20”—and onto the main drag past souvenir shops with names like “Alien Zone”, “Alien Encounter”, and “Area 51”, it was hard not to feel like P.T. Barnum’s proverbial sucker. The town’s intriguing role in nuclear history serves as a foothold for the moneymaking myth.

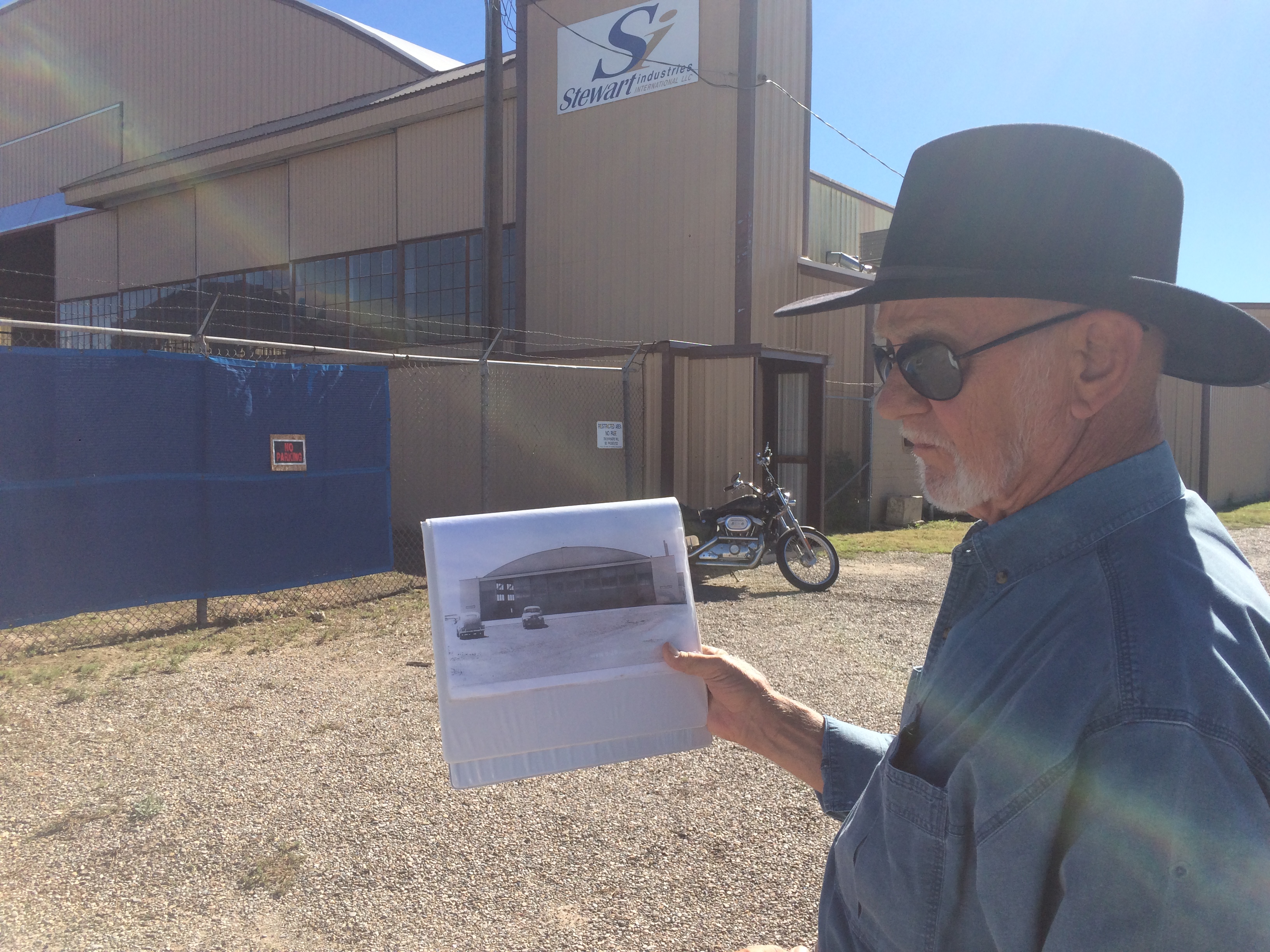

Thirty minutes later I’m waiting alone in the corner of a deserted parking lot just off the downtown strip—it’s the prearranged meeting point for my next close encounter with Roswell. A white GMC SUV pulls up, and a man dressed all in denim, with dark sunglasses and a black cowboy hat steps out—it’s gotta be him. I’ve arranged a private tour of the city with noted UFO researcher Dennis Balthaser, a true-believing local and retired civil engineer who’s been investigating and writing about the Roswell Incident since the 1980s. He used to work at the UFO Museum until 1998 when he says sensationalism aimed at getting people in the door began to trump a commitment to facts (his email handle is “truthseeker”). We climb into his SUV and he opens by asking what I know about Roswell. I explain that as a 90s child, I grew up with the story and signaled my openness with the classic Mulderism “I want to believe”. I also mentioned my own research in space history and was upfront that my project was being funded through a NASA Fellowship. “Do you know what NASA really stands for?” he asked with a sly grin. “Never A Straight Answer,” I fired back, to his instant delight (I’ve listened to enough late-night paranormal talk radio to know that old chestnut).

Fig 2.

As we drove past points of interest around town—the former site of The Roswell Daily Record, which published the initial “captured flying disc” report, some houses once owned by various military officers connected to the story, and a number of government buildings—he produces a three-ringed binder containing laminated glossy photographs that illustrate his account of the events of July, 1947. The last destination on the two hour tour is a hanger (“hanger 84” to those in the know) at the old site of Roswell Army Airfield at the edge of town, where eyewitness accounts claim the recovered craft and dead alien bodies were stored before being spirited away to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. Renamed Walker Air Force Base in 1948, and permanently shuttered by President Lyndon B Johnson in 1967, the place now serves as a massive wrecking yard for hundreds of commercial airliners. As Balthaser regales me about the alleged events in the hanger, a worker nearby swings a giant crane claw, tearing into the body of a decommissioned 747.

Balthaser opens up to me about the biggest problem facing his research: the passing of time. Development around Roswell has led to the tearing down of buildings important to the story of the incident, and Balthaser is upset that the city has failed to preserve these structures, which he considers to be historically significant, or even mark their former place with a plaque—all part of the cover-up, according to him. Buildings are disappearing, and so are people. Facing the same problem as historians of World War Two, Balthaser’s eyewitnesses are gradually dying off. Just a few months before my visit, Glenn Dennis, the local mortician back in 1947 who had lots of juicy stories, passed away. Balthaser also reveals that he’s one day shy of his 74th birthday, and doesn’t expect to live to see a resolution to the mystery. There’s frustration in his voice because he’s convinced that hard evidence—pieces of alien debris pocketed by sneaky soldiers tasked with the cleanup—must be squirreled away in attics around town, their provenance and significance now lost on a younger generation. I ask him what he thinks about the fleet of gaudy gift shops downtown, and the saturation of the iconic little green man: “That’s all part of the cover-up—besides, we know for a fact they were grey, not green.”

Fig 3.jpg

My last stop—the Roswell Museum and Art Center—provides some relief from the ET barrage, and a bit of perspective. While the rest of town is overrun by aliens, there is clearly an embargo here; nary a UFO or almond-eyed creature in sight. It feels like an oasis—the last bastion left outside the clutches of myth. Modern southwestern art adorns the walls, but I’m here specifically to investigate a strand of local space history, long eclipsed by flying saucer fever. It was in the secluded plains around Roswell in 1930 that American rocket pioneer Robert H. Goddard experimented with liquid-fuelled rockets guided by gimbal-mounted gyroscopes. The museum features a long, walk-through recreation of his workshop, and outside the museum stands a large statue depicting a life-sized Goddard positioned below a towering rocket gantry, his finger on the launch button, his gaze turned skyward. But this intriguing episode in the history of technology is obscured by the Roswell myth. Mention “Roswell” and no one thinks of Goddard, rocketry, or any terrestrially-developed space technology.

As historians we are taught to eschew myths like the Roswell UFO incident. But rather than treating them like intellectual mineshafts or toxic waste dumps—to be avoided at all cost lest we lend them credibility or become tainted ourselves—these tales can be useful entry points for legitimate enquiry, and moreover, signs of marginalized episodes ripe for investigation.

After all that, it was time for me to crash in Roswell, and reflect on my time in a city struggling with a run-away story about alien technology and government cover-ups—split at the seams between those looking to profit off little green men, self-professed “truth-seekers” like Balthaser, and people interested in purging the stigma of myth and restoring Roswell’s quainter identity as “the Dairy Capital of Southeast New Mexico”.

Jordan Bimm is a PhD candidate in Science & Technology Studies at York University in Toronto where his research focuses on the construction of the American astronaut in early cold war space medicine and space psychology. He is the recipient of the HSS/NASA Fellowship in the History of Space Science, 2014-2015, and in 2015-2016 he was a visiting student in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at Cambridge.

[1] As Ronald A. Schorn once wrote in a book review, “No reader of Isis is immune from the possibility of being asked sometime, somewhere, by someone, ‘Do you believe in flying saucers?’ ‘Are aliens visiting Earth?’ or, more to the point, ‘What about Roswell?’”