From “Snow Eagle” to “Ban the Tan:” Aviation and Canadian Climatic Identity

Technology’s Stories vol 5, no. 2 – doi: 10.15763/JOU.TS.2017.5.2.03

In late 1952 or early 1953, a man from California travelled between Edmonton and Vancouver with Trans Canada Air Lines, now Air Canada. He had such a miserable time that he left a comment card behind after his flight, complaining:

“Today’s flight from Edmonton to Vancouver was so blame cold…62 degrees is not fit for man or beast. On the other hand, it apparently was OK for the Canadians (no slur intended)…I should have worn woolen sox, heavy underwear, and a sweater. The least you could do would be to warn us…of your frigid intentions, so we could prepare for the ordeal. Other than that, the flight was fine. You have excellent pilots and capable Stewardesses (but probably cold-hearted).”[1]

This comment, printed under the pseudonym “Warm-Blooded” in TCA’s employee newsletter, has two major implications. One is the suggestion that the Canadian crew and passengers were more comfortable in the ambient temperature than the others on board. The other implication is that it was the temperature of the airplane that made him uncomfortable. The airplane in question was TCA’s newest airliner, the Canadair DC-4M2 “North Star,” which had been in use on nearly all the airline’s major routes since the late 1940s and was almost exclusively used by Canadian operators.[2] Which was better suited to the cold: Canadian machines, Canadian bodies, or both?

Aviation has been a key technology in Euro-Canadian self-fashioning, largely due to the nation’s size and seemingly impenetrable North.[3] Marionne Cronin, Stephen Bocking, and Jonathan Vance have all shown how Canada’s Arctic was made legible to the state by aerial surveying. Jeanne Haffner’s work on city planning also suggests that the airplane, or at least aerial view, could stand in for social order.[4] The relative ease with which aviation knitted together distances was especially resonant in Canada, since Canada’s size was (and still is) both a point of national pride and a perceived barrier to mobility. Furthermore, everyday exposure to aviation, especially during and after the Second World War, was shaped by state actors who built a discourse of nature, technology, and nation in which airplanes were positioned to both highlight and transcend Canadian geography.

Canadian bodies mattered to the story too. Confederation-era intelligentsia argued that Canadian winters awakened a long-lost Norse-ness that had lain dormant in the temperate British climate. Natural historian and politician R. G. Haliburton argued in 1869 that the great races of history—the Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians—were not-so-great because they all fell to invaders from the North; being northern meant being a “hardy, a healthy, a virtuous, a daring, and if we are worthy or our ancestors, a dominant race.”[5] This was almost a subversion of the climatic and racial sciences used to justify European imperial expansion into tropical places, which suggested that certain types of civilizations emerged in certain environments. Furthermore, Gillian Poulter has shown that through the nineteenth century, winter sports such as tobogganing and snowshoeing helped everyday Canadians self-identify as cold-weather people, as well as a nation unique from Britain and the United States more generally.[6] This winter performativity and winter mythmaking combination has not entirely disappeared. The winter carnivals that emerged through the late nineteenth century remain major tourist draws. Basketball fans chant “We the North” at Toronto Raptors games, and I often get asked by well-meaning Oklahoma locals how cold it is “in Canada right now.”

A definitive symbolism of linking Canada’s far-flung regions by airplane emerged in the interwar period. The trans-Canada airway, a cross-country network of airfields providing radio navigation, became a symbol of national unity during its construction through the 1930s. Unlike nineteenth-century transcontinental railroads, however, there was no commemorative “last spike” to be sold in gift shops, no visual cues of the route besides the airports and radio towers, and no modification to the landscape, as least nothing on the scale or rail or road. Even without these material manifestations, the symbol was evocative; municipalities fought to be part of the network, and citizens in smaller cities such as Halifax looked on jealously as rival towns—Saint John, New Brunswick, in Halifax’s case—built up their aviation infrastructure to impress state actors.[7] The airway was promoted with the sort of fanfare that would not have been out of place at Confederation in 1867, complete with claims that “a new map of the Dominion has been made…in which the time factor had replaced distance.”[8] The airplane, by virtue of its space- and time-shrinking abilities, was considered to be especially suited to Canada, where the nation’s huge distances had been an obstacle to economic, social, and political unity.

Aviation didn’t just highlight the spatial dimensions of Canadian-ness; it also underscored the aspects of nationalism tied to climate. Over the course of the twentieth century, aviation technologies both supported and subverted Canadian cold-weather identity. Interwar “bush pilots,” for instance, servicing growing northern communities by surveying, firefighting, and transporting supplies, became Canadian folk heroes. Their exploits, from inaugurating new routes to surviving accidents, represented the “real romance of transportation,” as a newspaper report on pilot Clennell “Punch” Dickins claimed in 1929:

“Figure, if you can, that big Fokker [airplane,] hurtling through Arctic skies, with flying temperatures of fifty or more degrees below zero—bucking the terrific winter tempests of that bleak and frozen land—and carrying, with the regularity of a crack trans-continental train, passengers and express between points that today are weeks and weeks apart.”[9]

Bush pilots did the very real work of bringing the comforts of the south (such as mail, vaccines, and catalogue shopping) to the North. They also did the symbolic work of making all of Canada legible to southern Canadians seeking homegrown heroes and cultural connections to a seemingly inaccessible and distant Arctic.[10] The “ingenuity” of the “old-time bush-pilot,” as CBC reporter Harold Kemp called it in the 1950s, was also a tie to Canadian climatic identity, since the ability to respond to Northern crises was often attributed to the pilots’ Canadian-ness. Kemp reported on the story of Saskatchewan pilot Bill Windrum, who salvaged his engine oil after a crash by melting the snow upon which it had spilled and skimming off the oil as it rose to the top.[11] Nova Scotia-born pilot Elmer Fullerton attempted to sell the story of a 1921 crash in which he repaired his propeller using dogsled skids and moose-hide glue to the editors of Flying magazine in 1952 by claiming that “this is the only instance in aviation history where a propeller was made by hand in BUSH country and used with complete success.”[12] When Dickins retired in 1966, the Edmonton Journal listed his “other names:” “the Northern Indians tagged him with Snow Eagle, the northern whites White Eagle, [and] newsmen Flying Knight of the Northland.”[13]

FIGURE 1: Bush pilot Clennell “Punch” Dickins (in cockpit with engine cover,) and crew on the first airmail flight to Fort Simpson, Alberta in 1929. Dickins labelled the back of the photo, “Getting started – after over night temperature of -56 F – below zero!” Punch Dickins Papers, Bruce Peel Special Collections, University of Alberta.

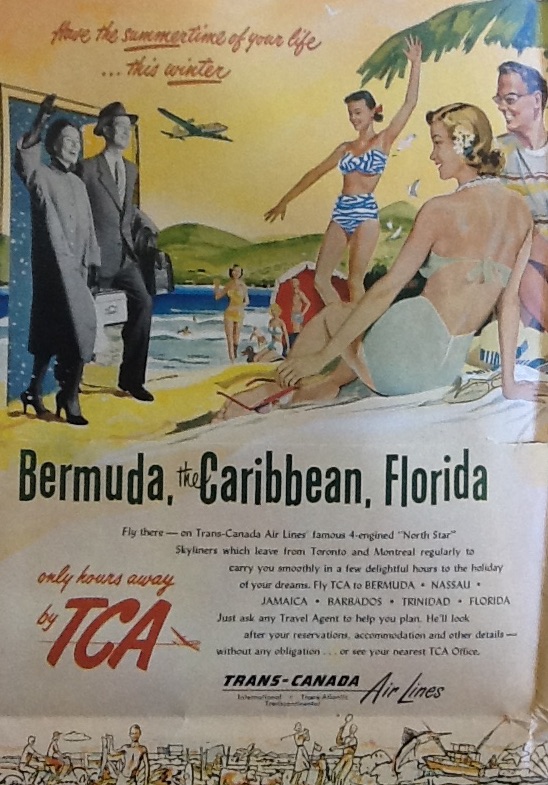

This triumphalist narrative connecting Canadian climates, Canadian pilots and Canadian machines began to erode once air travel became accessible to everyday Canadians. Trans Canada Air Lines was created by Act of Parliament in 1937, but it wasn’t until after the war that the airline began to position itself as a part of modern transportation infrastructure, featuring its new fleet of purpose-built “North Stars.” By the time Warm-Blooded was taking his chilly flight to Vancouver, “North Stars” were employed on every major TCA route, including what Air Canada still calls “sun destinations.” These destinations, which included Bermuda, various Caribbean spots such as Jamaica and the Bahamas, and several Florida cities, were promoted as temporal rather than geographic opposites to Canada. This is an important distinction, since wintering in warm places, which had been a longstanding staple of elite travel but was still a novelty for everyday Canadians, flew in the face of nationalist myths in which living through harsh winters was what made Canadians great. Rather than suggesting that passengers trade Canadian winter for the winters they might find elsewhere, early “sun destination” promotions at TCA claimed that they might exchange Canadian winters for Canadian summers. Advertising that Bermuda had “June in January” maintained Canadian winters while still selling a new service. It was still January in Bermuda, just the same as it was in Toronto or Montreal, but framing “sun destination” travel as moving through time rather than space meant that passengers, and the state entities building the narrative, could dodge the question of what might happen to Canadian national identity if January could be entirely avoided.

FIGURE 2: This 1951 Trans Canada Air Lines advertisement suggests that stepping between seasons is easy with the help of their “famous 4-engined ‘North Star’ Skyliners.” Air Canada Collection, Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

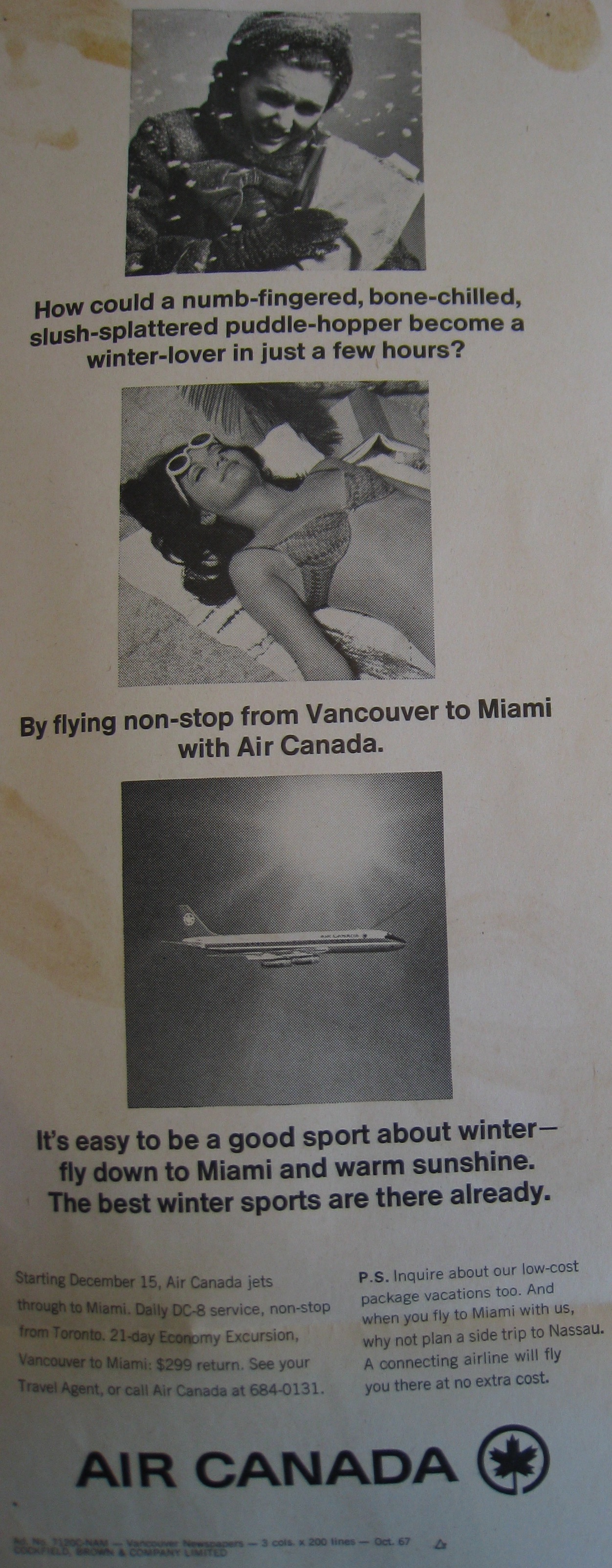

Once “sun destination” travel became commonplace, however, the tightrope between maintaining winter identity and leaving it behind snapped. Once introduced at TCA in the late 1950s, jet power transformed air travel into mass transit, and the airline essentially gave up on being delicate with Canadian climatic identity. In the Canadian context, the mundanity of air travel meant that the materiality of winter, which was already more easily mitigated by technological systems such as indoor heating and snowplows, could now be completely abandoned. Unlike climate controlled garages or indoor swimming pools, jet travel didn’t simply replicate summer conditions inside winter ones; it made it possible to completely ignore winter. Air Canada (as the airline was called in English starting in 1965) promotions for “sun destinations” in the jet age reflect this rhetoric of abandonment, suggesting that the only way to be a “good sport about winter” or a “winter-lover” was to travel somewhere warm during that season.[14] Unlike the promotions from the previous decade, these sorts of advertisements promoted an entirely new type of winter.

FIGURE 3: An Air Canada advertisement for the new Vancouver-Miami service in 1967. This ad was reproduced for several different regional markets, including Halifax and Toronto, with the same text. Air Canada Collection, Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

The draw of the tropics—so strong as to be insidious—seemed to be overtaking Canadian geographic and climatic pride. One 1970 Air Canada brochure, for instance, encouraged travelers to join “Club Calypso,” the airline’s frequent-Southern-fliers club, by calling it “Air Canada’s secret society of sun-worshippers.” And after listing all the Club Calypso destinations, the brochure provides “one warning: each is out to win your heart and soul—to become your perennial ‘place in the sun.’ So take heed, hedonists!” [15] Once they drew Canadians in, it appeared, “sun destinations” might not let them leave.

This rhetoric reflects an implicit change in the way space and time were perceived and experienced in the “modern” (or perhaps “postmodern”) world, suggesting that place may have become less central to national identity. This produced some anxieties in Canada, since a century of nationalism had been built on the folklore of harsh conditions and character-building winters. For example, Member of Parliament John Crosbie suggested in a 1977 session of Parliament that:

“All of us have heard of the ‘ban the bomb’ campaign. What we need is a ‘ban the tan’ campaign. Every Canadian who dares to go south next winter and returns to Canada with a tan should be ostracized…If hon. Members get a tan from the lights in this Chamber, we can explain that.”[16]

Although ostensibly about tourism dollars—Crosbie is mostly concerned about a large travel deficit in which foreign tourists spent less in Canada than Canadians spent abroad—Crosbie articulates a concern that had plagued intelligentsia in the jet age: how to maintain a national identity based on geography and climate when they were so easy to abandon. There were plenty of ways to travel south in the 1970s, but Air Canada encompassed all the places in which a Canadian might get a tan (you can’t drive to Bermuda!) and still fell under the arms-length jurisdiction of the federal government.

If we see aviation in the Canadian context as something David Nye might call a “technological creation myth,” then it’s no surprise that there are narratives and counter-narratives. This was not simply a matter of Canadians abandoning winters because technologies such as air travel made the material realities easier to escape. This was, instead, a consequence of the changing rhetoric of space and time inherent in twentieth century modernity; Canadian national identity was (and still is) so tied to geography and climate that state actors needed to find a delicate balance between celebrating Canadian winter and celebrating Canadian technological skill in overcoming winter. This was not always a successful balance, as this whirlwind tour of civilian aviation history clearly shows. Aviation had the potential to transcend space and time, bringing Canada’s far-flung coasts closer together while at the same time making it easier to take a quick fling in another place. It brought the North into the popular imagination, but also brought the South by increasing access to “sun destinations.” And it made everyday Canadians wonder how much of their nationalism was tied to being truly cold-hearted (no slur intended.)

Blair Stein is a Ph.D. Candidate in History of Science, Technology, and Medicine at the University of Oklahoma. Her dissertation examines how aviation, especially air travel, was a site in which Canadians negotiated modernity and nationalism, especially the aspects of nationalism tied to climate and geography. Her work has appeared in Technology and Culture, the Journal for the History of Astronomy, and an upcoming edited volume on Science, Technology, and the Modern in Canada. She was born and raised in Ottawa, Canada and misses the winters terribly.

Notes

[1] “What Others Think of Us—Warm-Blooded.” Between Ourselves January 1953, 3

[2] North Stars were used by TCA, Canadian Pacific Airways, and the Royal Canadian Air Force. The British Overseas Airways Corporation bought a few, but they were not widely used.

[3] By “Euro-Canadian” in this context I mean non-First Nations or Inuit peoples.

[4] Stephen Bocking “A Disciplined Geography: Aviation, Science, and the Cold War in Northern Canada, 1945-1960” Technology and Culture 50:2 (April 2009): 265-290; Marionne Cronin, “Northern Visions: Aerial Surveying and the Canadian Mining Industry, 1919-1928” Technology and Culture 48:2 (2007): 303-330; Jeanne Haffner, The View from Above: The Science of Social Space (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013); Jonathan Vance, High Flight: Aviation and the Canadian Imagination (Toronto: Penguin Canada, 2002).

[5] Robert Grant Haliburton, The Men of the North and Their Place in History (Montreal: John Lovell, 1869), 10.

[6] Gillian Poulter, Becoming Native in a Foreign Land: Sport, Visual Culture, and Identity in Montreal 1840-1885 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009).

[7] Vance, High Flight, 170-180.

[8] Canadian Aviation, April 1939, quoted in Vance, High Flight, 179.

[9] “Air Service From Waterways Links Simpson to Steel,” Edmonton Journal, January 8 1929.

[10] Caroline Desbiens, in Power from the North: Territory, Identity, and the Culture of Hydroelectricity in Quebec (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2013) shows how hydroelectric development in northern Quebec served a similar purpose inside the changing context of late-twentieth century Quebec nationalism.

[11] Harold Kemp, “The Old-Time Bush-Pilot,” undated manuscript (c. 1950s.) Elmer G. Fullerton fonds, MG30-A60, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa. Hereafter referred to as LAC.

[12] It’s unclear if Flying ever accepted his story, but it appeared in men’s magazine True in 1960. Letter from Elmer G. Fullerton to the editor of Flying magazine, 13 May, 1952. Elmer G. Fullerton fonds, MG-30 A-60, volume 1, LAC.

[13] Dwayne Erickson, “Snow Eagle Folds His Wings,” Edmonton Journal, June 3 1966, 59.

[14] Godefroy Desrosiers-Lauzon’s Florida’s Snowbirds: Spectacle, Mobility, and Community Since 1945 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2011) is the definitive English work on Canadian travel to Florida, although he mostly focuses on automobile tourism.

[15] “Island Vacations Winter 1970/1971,” Air Canada fonds, RG-70, volume 117-15.4, LAC.

[16] It was nice of him to give Members of Parliament an easy “out” here. House of Commons Debates, 30th Parliament, 3rd Session: Vol 1 (October 25 1977): 252.